Why Cape Canaveral?

The answer to why rockets launch from Florida and not elsewhere (although that's changing)

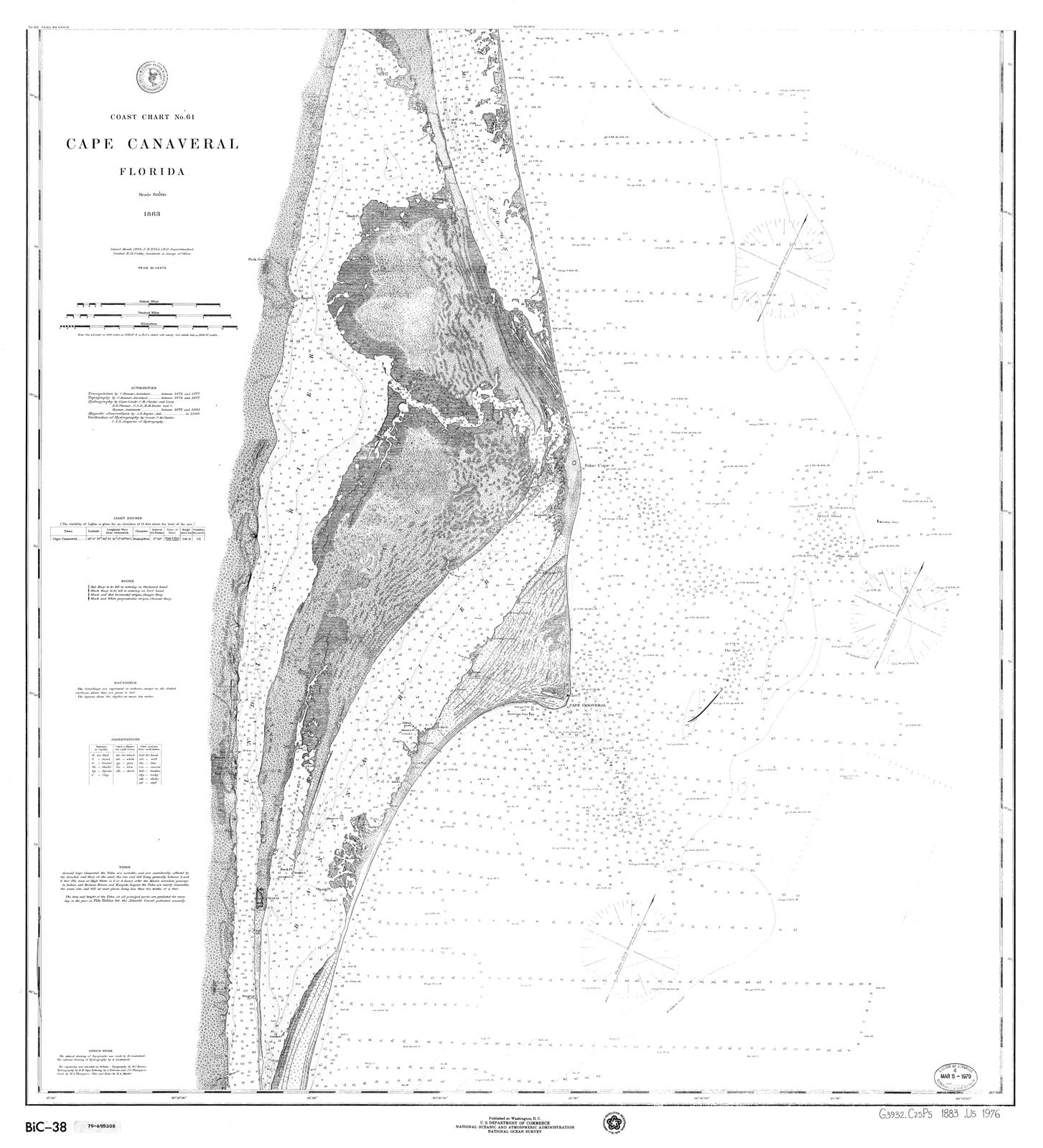

An 1883 United States Coast and Geodetic Survey map of Cape Canaveral. Source: University of South Florida.

Why Cape Canaveral?

During my years doing lectures and tours at Kennedy Space Center, it was one of the most common questions I was asked.

Lots of myths are out there, with few knowing the real reasons.

So let’s travel back in time.

Once Upon a Time …

Before answering “why,” let’s answer “what.”

Take a look at the 1883 map at the top of this article. Cape Canaveral is the peninsula that juts out from a barrier island east of the Banana River. (Yes, we have no bananas. The origin of the name is unclear.1) West of the Banana River is Merritt Island, and west of that is the Indian River. To the west of the Indian River is the Florida mainland.

The term “Canaveral” is believed to have originated from Spanish explorers who found the Cape in the early 16th Century. “Canaveral” is believed to mean a place overgrown with canes or reeds; it’s sometimes translated as “canebrake.”

Indigenous tribes roamed the area, primarily the Ais. As you might suspect, the Ais and European colonials had their own long and occasionally violent relations. By the 18th Century, indigenous peoples had largely disappeared from the Cape.

Cape Canaveral was a generally unpleasant place to live. The United States acquired Florida from Spain in 1822. A territorial legislative council divided Florida into counties; the future Space Coast was part of what was called Mosquito County, with good reason. In 1854, as white settlers tricked into the area, the county was subdivided into smaller counties. Cape Canaveral became part of Brevard County (named after Florida comptroller Theodore W. Brevard).

A map of the Gulf Stream drawn in the late 18th Century by Benjamin Franklin. Image source: Britannica.

The Cape was a handy navigational reference. For centuries, sailing ship navigators used Cape Canaveral as a visual reference. If the navigator spotted the Cape, he knew they were on course.

The US government built a lighthouse on the tip of the Cape in the late 1840s. It was eventually replaced in 1894 by a larger lighthouse that now resides about a mile inland. A small community grew up around the second lighthouse.

On the Banana River side, a small community called Canaveral began in 1883 with a post office and general store at a wooden dock. In the early 20th Century, homesteaders began to occupy the Cape. Dirt roads were plowed to connect the homesteads. Steamships were the primary means of accessing the Cape from the mainland.

Bridges were extended in the 1920s from the mainland to the barrier islands. Cape Canaveral could be accessed by automobile from Cocoa Beach to the south. Various investor groups lobbied the federal government for funding to build a harbor in the bight south of the Cape. Nascent harbor plans were put on hold when World War II began.

Banana River Naval Air Station

The origin of space launches from Cape Canaveral traces back to World War II and the opening of a naval base south of Cocoa Beach.

In response to Nazi German aggression in Europe, President Roosevelt and Congress in 1938 directed the Secretary of the Navy to report on the need for additional bases along the US coasts. The report identified a site “in the lower reaches of the Banana River near Cocoa Beach” for a seaplane patrol base.

The Banana River Naval Air Station was commissioned on October 1, 1940. Bombing target sites were set up on Cape Canaveral and in the nearby Banana River. After the declaration of war against the Axis in December 1941, practice bombs were replaced with real ones. Training flights were supplemented with active duty patrols. Coastal patrols were replaced with anti-submarine patrols, as German U-boats attacked commercial shipping lanes in the same Gulf Stream waters once plied by sailing ships.

A squadron of Douglas SBD Dauntless naval scout planes fly near NAS Banana River during World War II. Image source: World War Photos.

After the war, the Navy began to discharge personnel from NAS Banana River. The base closed on October 1, 1947.

Von Braun Comes to Cape Canaveral

While NAS Banana River seaplanes patrolled for German U-boats, 4,800 miles (7,700 km) away in Peenemünde, Germany Dr. Wernher von Braun and his engineers were developing rocket technology. Although their origins traced back to a Berlin rocket club interested in peaceful uses, the German Army under Adolf Hitler mandated that their research be focused on “wonder weapons” such as the V-2 missile.

At the end of the war, von Braun and many of his engineers surrendered to the US Army. They were taken to an Army base in White Sands, New Mexico, not far from El Paso, Texas on the Mexico border. The Army found enough parts hidden around Germany to assemble about one hundred V-2s in New Mexico.

With more testing, von Braun and his team learned more about rocketry. Their missiles went higher, farther, and straighter. The rockets began approaching the limits of the test range at about 100 miles (160 km).

One infamous failure led to a search for a new test site. On May 29, 1947, a V-2 with an errant gyroscope launched the wrong way, heading south over El Paso into Ciudad Juárez, Mexico. The missile impacted near a cemetary outside the town, so it only killed people who were already dead.

The Pentagon appointed a committee to look for a new launch site. The committee looked for a place where tracking stations could follow a missile overhead, with either a ground-based station or a ship at sea, to capture performance data until it impacted downrange.

The three finalists were El Centro, California, Cape Canaveral, Florida and the Aleutian island chain. The Aleutians were eliminated due to bad weather.

The committee’s top choice was El Centro, on the Mexico border. Missiles would launch to the southwest over the Baja Peninsula. The president of Mexico, recalling the Ciudad Juárez incident, declined to grant overflight rights.

That left Cape Canaveral. Missiles would launch to the southeast, across the North Atlantic Ocean and the Caribbean Sea, where tracking stations could be placed on British-held islands. Navy ships could fill the gaps. NAS Banana River was reassigned to the Air Force, which renamed the facility Patrick Air Force Base.2

This map accompanied a March 1949 Associated Press article, illustrating the Pentagon’s search for a missile test site with a range of up to 3,000 miles. Image source: Newspapers.com.

Using eminent domain, the Air Force began to acquire land on the Cape. The new range, part of Patrick, was called the Joint Long Range Proving Ground (JLRPG) — “joint” because it would also be used by the Army and Navy, although the Air Force would manage the range.

Von Braun and his team left White Sands for a reopened chemical manufacturing facility in Huntsville, Alabama called the Redstone Arsenal. Their test missiles were trucked or flown to Patrick, then towed to the first launch sites on the tip of the Cape. The first launch was July 24, 1950, from Launch Complex 3 near the lighthouse.

A silent film compilation of the Joint Long Range Proving Ground and Project Bumper in 1950. Video source: Cape Canaveral Space Force Museum.

Let’s Talk About Orbital Mechanics

Okay, I know “orbital mechanics” sounds scary. It’s scary to me too. I have a political science degree, so I know nothing useful. But if I can explain it to me, I can explain it to you.

Orbital mechanics is relevant to this conversation because it’s not — at first, anyway.

Orbital mechanics is the study of the motions of artificial satellites and other space vehicles moving under the influences of gravity and other factors such as engine thrust. It’s akin to celestial mechanics, the study of the motions of natural celestial bodies.

The key word here is “orbital.” Satellites, space stations, and other payloads orbit Earth, for reasons we’ll discuss later.

But in 1950, orbital flight was not a military concern. The military branches were only interested in testing weapons of war. In the next decade, it was projected that the US might have an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) with a range of 3,000 - 5,000 miles (4,800 - 8,000 km). Von Braun and many civilian scientists knew the math of orbital mechanics, but in 1950 that wasn’t why the Cape was chosen. It was to launch ballistic missiles to the southeast across the Atlantic Ocean, flying over warships and tracking stations collecting data.

The advent of ICBMs gave hope to those who dreamed of orbiting artificial satellites one day. Here’s where we get into the physics and math.

To orbit Earth, an object must equal the pull of the planet’s gravity. The closer to Earth, the stronger its gravitational pull, so the object must travel faster. Launch with too slow a velocity, and gravity pulls the object back to Earth. Launch too fast, and the object flies off into space. But find just the right balance, and it remains circling Earth — what we call an orbit.

The Newton’s cannonball thought experiment illustrates how to achieve an orbit. Video source: Cosmos YouTube channel.

Today’s International Space Station orbits Earth at an altitude of about 250 miles (400 km). Do the math, and it works out that to remain in orbit the ISS must travel at about 17,500 mph (28,000 kph).

But which orbit?

A prograde orbit (also known as a posigrade orbit) means the object moves in the same direction that Earth rotates. If a rocket launches in the same direction Earth rotates, west to east, it gets a boost from the rotation, as if getting a running start.

A retrograde orbit means launching opposite Earth’s rotation.

A polar orbit means launching over Earth’s poles, at a 90° inclination — no boost from Earth’s rotation.

To prove none of this mattered in Cape Canaveral’s early days, remember that the military’s first choice for a launch site was El Centro, California. Missiles were going to launch to the southwest, against Earth’s rotation, over the Baja Peninsula. The objective wasn’t to orbit a payload, it was to record data from tracking stations before the missile impacted downrange (hopefully in the ocean). It was only after Mexico’s president denied overflight rights that the military chose Cape Canaveral.

Orbital mechanics came into play later in the 1950s. In the spring of 1950, an informal group of American and British scientists decided to stage a global effort to study the geology and physics of Earth, which eventually came to be known as the International Geophysical Year. Their hope was to adapt a US ballistic missile to launch and orbit a small satellite. Depending on the rocket, it could send a nuclear bomb anywhere from a couple hundred to several thousand miles but, with a smaller and lighter satellite, it could orbit its payload with a longer engine burn.

The Eisenhower administration received proposals from all three military branches, and selected the Naval Research Laboratory’s Project Vanguard. Working with the Martin Company, the NRL planned to launch its Vanguards from the Cape’s Launch Complex 18.

For the first time, orbital mechanics came into play.

Vanguard 1’s launch trajectory took it out over the Atlantic Ocean, so its stages could fall into the water and not on land. Image source: Naval Research Laboratory via Drew Ex Machina.

In the above illustration, note that Vanguard launched to the southeast. Not only did it take advantage of Earth’s rotation, but it also launched over the Atlantic Ocean. If the rocket blew up, it fell into the ocean. If it didn’t blow up, its stages once expended fell into the ocean. As it flew, tracking stations downrange tracked its progress.

Vanguard 1’s orbit was not a pure prograde orbit. It orbited at an inclination of 34.25° to the equator, which meant it would travel over parts of the northern and southern hemispheres.

Vanguard 1’s 34.25° orbit on December 22, 2024 projected on a Mercator map. Image source: Satflare.

Vanguard 1 was delayed by technical problems and an infamous launch failure. President Eisenhower gave von Braun’s Army Ballistic Missile Agency permission to launch an improvised satellite, called Explorer 1, atop a modified Redstone missile. Explorer 1 launched from Cape Canaveral on January 31, 1958. Vanguard 1 launched from nearby on March 17, 1958. Both launched to the east, out over the ocean.

Why Merritt Island?

On May 25, 1961, President John F. Kennedy proposed that the United States land a man on the Moon by the end of the 1960s.

That proposal evolved into what came to be known as Project Apollo.

But from where would it launch?

Eight launch sites were considered, including an offshore platform, the Bahamas, Brownsville, Texas, White Sands, Christmas Island in the Pacific, the island of Hawaii, and at Cumberland Island in Georgia. The Canaveral area had overwhelming advantages, one being the already existing missile range with experienced personnel.

The Cape had an orbital mechanics advantage over Cumberland Island and any other potential sites further north. The closer a location is to the equator, the faster it rotates around Earth’s axis. Both the poles and the equator rotate around the axis every 24 hours, but a point on the equator must go much faster, while a point near a pole rotates very slowly. This is called rotational speed.3

Cape Canaveral was the logical choice, but was already built out or had sites designated for future programs, so NASA used eminent domain to buy land on north Merritt Island.

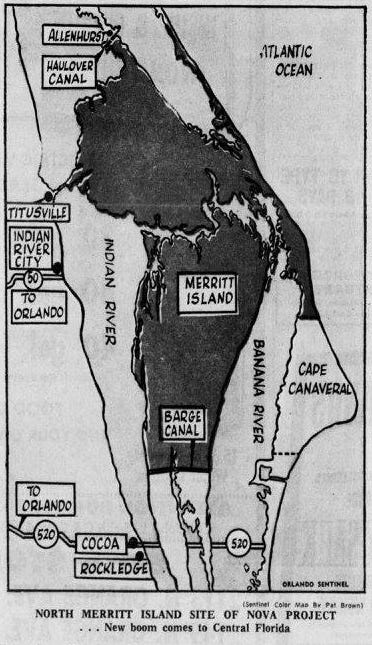

Page 1 of the August 25, 1961 Orlando Sentinel had a map depicting the proposed location of what was still being called Project Nova by some. Image source: Newspapers.com.

A California Launch Site

Vandenberg Space Force Base near Lompoc, California has been used by the US military since late 1958 for testing ballistic missiles. As with the early days at the Cape, these missileers didn’t care about orbital mechanics. They launched their missiles out into the Pacific.

In the satellite era, Vandenberg became the preferred site for launch payloads into a polar orbit. Rockets launched to the south, out over the ocean in case they failed. Polar launches were impractical at Cape Canaveral, because launching to the north or south took the rockets over populated areas. Many reconnaissance satellites are launched into a polar orbit; as Earth rotates beneath them, they can map the entire planet.

In the early days of the Space Shuttle program, NASA planned to station an orbiter at Vandenberg for flying military missions. These flights typically would have placed payloads into a polar orbit. After the Challenger accident in January 1986, the Air Force decided to transition to expendable rockets, launched either from Vandenberg or the Cape, depending on the needed orbit.

Cape Canaveral Today

The Joint Long Range Proving Ground remains part of Patrick, although the names have changed. The JLRPG is now Cape Canaveral Space Force Station, part of Patrick Space Force Base.

Despite summer lightning storms and the occasional hurricane4, the Space Coast remains the premier place to leave planet Earth.

The ISS orbits Earth at a 51° inclination to the equator. That angle was chosen when it was decided to built a station serviced by both the United States and Russia. The orbit passes over both the Cape, and the Russian launch site at Baikonur, Kazakhstan. It’s also serviced by occasional Northrop Grumman Cygnus commercial cargo vehicles launched from Wallops, Virginia.

SpaceX has demonstrated the capability to launch southerly polar orbits from Cape Canaveral. Its Falcon 9 has engines that gimbal so it can alter its course and avoid flying over populated land. Since 2015, SpaceX has the capability to land their rockets at the Cape, an astonishing feat that von Braun and his engineers might have considered a near-miracle, although it’s only physics.

Why Cape Canaveral? Now you know.

According to local legend, bananas once grew along the river. That makes little sense as bananas originated in Southeast Asia. The marshy lands along the river are poor for growing bananas. The more likely explanation is that some thought the river was shaped like a banana.

Major General Mason M. Patrick was chief of the American Expeditionary Force's Air Service in World War I and postwar head of the US Air Service.

To calculate a location’s rotational speed, all you need is its latitude. The vCalc website has a page for calculating rotational speed.

Most critical structures at Kennedy Space Center are designed to withstand Category 3 to 5 hurricanes. Theory and reality, of course, may differ.