What is Project Artemis?

NASA plans to send four astronauts around the moon sometime this spring. The mission traces back to an Obama-era program cancelled by Trump.

Artemis I launches on November 16, 2022. Image source: NASA.

Sometime this spring, NASA hopes to send astronauts to the moon for the first time since 1972.

The mission is called Artemis II, part of a NASA program called Project Artemis.

Let’s address some basic questions you might have about this mission.

Why Did NASA Stop Going to the Moon?

On May 25, 1961, addressing a joint session of Congress, President John F. Kennedy proposed:

I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth.

Kennedy didn’t propose building Starfleet. He didn’t propose a permanent lunar base. He did propose sending one man to land on the moon, and bringing him back.

NASA eventually planned fifteen Saturn V launches. The early missions were to test the hardware and software. Landing attempts were to begin with Apollo 11, meaning NASA had ten chances to land humans on the moon.

Kennedy’s challenge was met on the first try. Mission accomplished.

What to do with the remaining nine missions?

After the three Apollo 13 crew members were nearly lost in April 1970, President Richard Nixon decided to truncate the program. Administration officials convinced him to let missions continue through Apollo 17, dropping three missions.

When Did NASA Start Planning to Return to the Moon?

Opinion polls never were all that strongly in favor of the crewed lunar program.1

By the late 1980s, however, several space advocacy groups had formed — the National Space Society, the Space Studies Institute, The Planetary Society, the Space Foundation, and the Space Frontier Foundation. Collectively they were lobbying Congress and the White House for their pet causes. Some wanted a return to the moon.

On July 20, 1989, the 20th anniversary of the Apollo 11 landing, President George H.W. Bush proposed what came to be known as the Space Exploration Initiative. NASA prepared a “90-Day Study” that envisioned completing the space station, followed by “a return to the Moon to stay, and a subsequent journey to Mars.”2 Congress showed little interest, so the proposal died.

Nearly a year after the Columbia accident, President George W. Bush on January 14, 2004 announced what became known as the Vision for Space Exploration. Bush proposed a Crew Exploration Vehicle, which evolved into the Orion crew capsule. He also set the goal of a crewed lunar return by 2020. That eventually became known as Project Constellation.3

A year later, Michael Griffin became NASA administrator. Griffin redesigned Constellation into what he called “Apollo on steroids.” By the time Bush and Griffin left office on January 20, 2009 Constellation was far behind schedule and way over budget.4

Did President Obama Cancel the Moon Program?

Here’s where it gets complicated.

Aware of Constellation’s delays, President Barack Obama convened a study group called the Review of US Human Spaceflight Plans Committee.

Delivered in October 2009, the report began:5

The U.S. human spaceflight program appears to be on an unsustainable trajectory. It is perpetuating the perilous practice of pursuing goals that do not match allocated resources.

Constellation was so fundamentally flawed that a crewed lunar landing was unlikely until at least the late 2020s.

The heavy-lift vehicle, Ares V, is not available until the late 2020s, and there are insufficient funds to develop the lunar lander and lunar surface systems until well into the 2030s, if ever.

The report was the basis for the Obama administration’s Fiscal Year 2011 proposed NASA budget. The proposal shocked the space establishment. The administration proposed cancelling Constellation, at a time of high unemployment due to the Great Recession. No longer would NASA issue cost-plus contracts that guaranteed contractors a profit regardless of performance. NASA instead would use competitively bid fixed-price contracts to purchase crew and cargo deliveries to the space station, which would be extended to at least 2020. Billions would be invested in developing new technologies for sending crews beyond Earth orbit. Crewed missions would be preceded by robotic explorers to the moon and Mars.6

Congress hated it. After almost a year of political fights, a compromise emerged which replaced Constellation with a new booster called the Space Launch System.

For the first time in NASA’s history, a launch vehicle was designed not by the agency, but by members of Congress. The 2010 NASA Authorization Act told the agency how to build it. Congress required NASA to use existing shuttle and Constellation contractors to build SLS, without competitive bids. Existing technologies, infrastructures, and employees had to be used as well, unless no other option was possible.7

Congress told NASA to build it, but not what to do with it. That was left to the president.

On April 15, 2010, in a speech at Kennedy Space Center, Obama proposed that, rather than an Apollo redo, NASA send astronauts to rendezvous with an asteroid as a first step towards sending crews to Mars in the 2030s.8

A 2016 NASA animation demonstrating a possible crewed asteroid redirect mission. Video source: NASA YouTube channel.

Congress didn’t care much for that idea either. The program was defunded during the first year of Donald Trump’s first administration.

The Obama administration didn’t write off the moon. They left lunar exploration to the private sector, through a program called NextSTEP — Next Space Technologies for Exploration Partnerships. NextSTEP is providing many of the technologies that are part of Project Artemis, such as the Gateway lunar orbital space station, a lunar base, and exploration rovers.9

Who Created Project Artemis?

President Trump’s first term began on January 20, 2017. Almost a year later, he issued his Space Policy Directive-1, amending Obama’s 2010 national space policy. It deleted Obama’s 2030 Mars target date, and replaced Obama’s “far-reaching exploration milestones” paragraph with an order directing “the return of humans to the Moon for long-term exploration and utilization, followed by human missions to Mars and other destinations” with no target dates.

Trump revived the National Space Council in June 2017.10 The council, which is an advisory body, was in NASA’s 1958 founding charter. Some presidents have used it. Some have not.

At the US Space and Rocket Center in Huntsville, Alabama on March 26, 2019, Vice President Mike Pence, who chaired the council, announced that, “it is the stated policy of this administration and the United States of America to return American astronauts to the Moon within the next five years.” The first mission should land at the moon’s south pole. The US should establish a sustained presence at the pole, evolving technologies for a distant Mars mission.11

Pence declared:

If NASA is not currently capable of landing American astronauts on the Moon in five years, we need to change the organization, not the mission.

If you check your calendar, in March it will be seven years since Pence set that five-year deadline. NASA now predicts its first Artemis lunar landing will be sometime in 2028.12 Tick tock.

Rep. Jim Bridenstine (R-OK) became Trump’s NASA administrator on April 23, 2018. In May 2019, Bridenstine announced that the lunar program would be called Project Artemis. In Greek mythology, Artemis was the twin sister of Apollo.

So who created Project Artemis?

The Orion crew capsule traces back to the W. Bush administration. The Space Launch System traces back to the 2010 NASA authorization act compromise between the Obama administration and Congress. The Obama administration proposed an asteroid mission as a stepping stone on the way to Mars, as well as creating the NextSTEP program to develop commercial technologies for cislunar operations and beyond.

The first Trump administration cancelled the asteroid mission and directed NASA back to the moon as a more immediate priority. NextSTEP was redirected to this goal. The National Space Council in March 2019 recommended a lunar base at the south pole. Administrator Bridenstine announced the name Artemis in May 2019. Artemis, essentially, is an umbrella name for SLS, Orion, and NextSTEP, with new specific missions and objectives. The Biden administration continued Artemis.

How Does SLS Compare to the Saturn V?

A comparison of the Space Launch System to the Saturn V and the Space Shuttle. Image source: NASA.

SLS technology descends from both the Saturn V and the Space Shuttle.

The Saturn V first stage used RP-1 kerosene as a fuel, but the upper stages used liquid hydrogen (LH₂). In the 1960s, LH₂ was still experimental, but the Saturn program matured its use.

The Space Shuttle’s orange external tank carried LH₂ as a fuel. When Congress mandated in 2010 that SLS be based on Shuttle technology, that meant that its core stage would also use LH₂ as a fuel.

Solid rocket booster lineage traces back to military missiles. The congressional mandate also required NASA to use the SRBs in the SLS design.

Subsequent reviews have questioned NASA’s cost estimates as well as the design constraints imposed by Congress. As early as 2011, an external review by Booz Allen Hamilton found, “Several technical risks exist that could have significant cost and schedule impacts.”13 In September 2023, the Government Accountability Office reported that NASA “does not plan to measure production costs to monitor the affordability of its most powerful rocket …”14

Senior NASA officials told GAO that at current cost levels, the SLS program is unaffordable.

How Does Orion Compare to the Apollo Spacecraft?

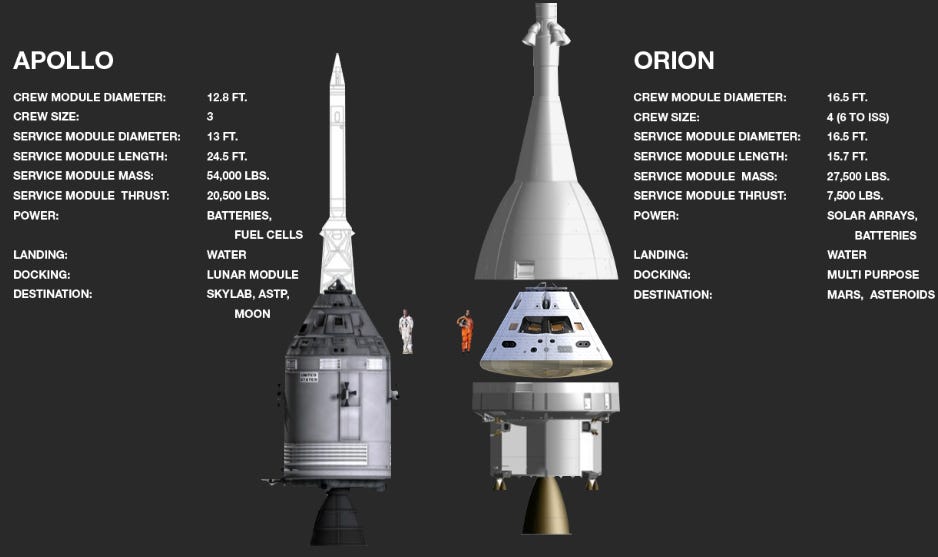

A comparison of the Apollo and Orion crew capsules. Image source: NASA.

At first glance Apollo and Orion are similar. Both are conical. Both have abort towers. Both have propulsive service modules. Both have heat shields that will ablate as the craft enters Earth’s atmosphere to land in the Pacific Ocean.

Apollo carried three crew members for up to 14 days, while Orion can carry four crew members for up to 21 days. Orion has about 60% more habitable space. Orion’s service module, built by the European Space Agency, will deploy solar panels to provide electrical power.15

A recent kerfuffle erupted over the safety of Orion’s heat shield. Because the Artemis I Orion suffered an unexpected loss of ablative material on atmospheric entry, NASA delayed Artemis II for further study. NASA believes that the Artemis II Orion can safely enter by changing its angle of attack. Retired astronaut Charles Camarda has been quite vocal in recent days about his disagreement with NASA’s conclusion.16

I was able to find major technical issues and false statements in a short 3-hour briefing presenting only the program side of the story and 1 day being allowed to review some of the technical issues that made me very troubled.

When Will Artemis II Launch?

SLS must launch only when Earth’s rotation and the moon’s position align to fit the mission profile. NASA has posted the below calendar to show potential launch windows from February through April. The earliest is February 6, although that’s unlikely.

NASA’s projected launch windows for Artemis II. Click the image to download a PDF of the schedule from the NASA website.

What Will the Astronauts Do on Artemis II?

The crew won’t attempt a landing. The lunar landers from SpaceX and Blue Origin won’t be ready for several years. That attempt is planned for Artemis III. Artemis II is projected to be a ten-day flight to test out systems and hardware. At its apogee, Orion will be 4,700 miles (7,500 km) beyond the far side of the moon, the furthest humans will have travelled from Earth.17

NASA videos showing the Artemis II mission profile and mission science objectives.

Roger D. Launius, “Public Opinion Polls and Perceptions of US Human Spaceflight,” Space Policy 19 (2003), 163-175.

“Report of the 90-Day Study on Human Exploration of the Moon and Mars,” NASA, November 1989.

“President Bush Announces New Vision for Space Exploration Program,” Washington DC, January 14, 2004.

Jason Davis, “‘Apollo on Steroids’: The Rise and Fall of NASA’s Constellation Moon Program,” The Planetary Society, August 1, 2016.

Norman R. Augustine et al, Seeking a Human Spaceflight Program Worthy of a Great Nation, Review of US Human Spaceflight Plans Committee, October 2009.

Competitive Space Task Force, “The Senate Launch System.”

“Press Release: Remarks of President Barack Obama at the Kennedy Space Center,” April 15, 2010, The American Presidency Project, UC Santa Barbara.

NextSTEP documents on the NASA website detail the various programs and contracts.

Federal Register, Executive Order 13803, “Reviving the National Space Council,” June 30, 2017.

National Archives, “Remarks by Vice President Mike Pence at the Fifth Meeting of the National Space Council,” Huntsville, Alabama, March 26, 2019.

NASA Artemis III webpage lists the launch as, “By 2028.”

Booz Allen Hamilton, “Independent Cost Assessment of the Space Launch System, Multi-Purpose Crew Vehicle and 21st Century Ground Systems Programs,” Executive Summary of Final Report, August 19, 2011, x.

Government Accountability Office, “Space Launch System,” GAO-23-105609, September 2023, highlights page.

NASA, Orion Reference Guide, 14, 30-32.

Eric Berger, “Is NASA’s Heat Shield Really Safe?” Ars Technica, January 9, 2026. Charles Camarda PhD Linkedin webpage, January 13, 2026.

Kathryn Hambleton, “NASA’s First Flight With Crew Important Step on Long-term Return to the Moon, Missions to Mars,” NASA Artemis webpage, April 8, 2025.