The Ups and Downs of Gravity

Is it possible to turn off gravity while on Earth? Not yet. You still have to leave the planet to float.

NASA astronaut Sunita Williams supervises Astrobee’s free-flying robot during a November 2024 experiment aboard the International Space Station. Image source: NASA.

“I just hate gravity. But gravity doesn’t care. It always pulls you down.” — Clayton Christensen

During the ten years I lectured at Kennedy Space Center’s visitor complex, a common question guests asked was:1

“Where’s the room where we can float?”

I finally realized they thought NASA somehow had the ability to turn gravity on and off.

It was my job to explain gravity to the masses (an oblique physics pun; stay tuned), so I decided I’d better learn to explain to a lay person all about gravity and orbital mechanics.

My mantra remains, “I have a political science degree. I know nothing useful. If I can explain it to me, I can explain it to you.”

So let’s try to explain it for our mutual benefit.

We know what gravity does. We don’t know what gravity is.

We can measure its results. Standing on Earth’s surface, toss a ball into the air. Eventually the ball will reach its apogee (an astronomy term meaning its farthest point from Earth), only to fall back to its perigee (its nearest point to Earth, such as your hand). Absent other factors, that fall is at an acceleration of 32.2 feet per second squared (9.8 meters per second squared).

But why does it fall? What force is pulling it down?

Einstein’s theory of general relativity suggests that, as some physicists describe it, gravity is an illusion. Gravity is a curvature of space-time, that is the three dimensions of height, length and width moving onward through the passage of time.

Massive objects cause space-time to curve, such as Earth moving through space. Image source: NASA.

Any object that has mass creates what we experience as a gravitational pull (a curvature of space-time). You and I have mass, so we exert a gravitational pull, but it’s so miniscule it can’t be measured.

Mass and weight are two different concepts. Mass is the amount of matter in an object. Weight is the force exerted by a mass as a result of gravity. Weight is experienced on Earth’s surface by an object at rest. The object will still have mass in a microgravity environment but it won’t have weight. Why?

The farther one object is from the other, the weaker the pull.

Another way to experience microgravity is to outrun the pull.

This can be illustrated by a thought experiment called Newton’s Cannon Ball, after physicist Sir Isaac Newton.

Newton’s Cannon Ball as illustrated by “Cosmos: A Spacetime Odyssey.” Video source: Cosmos YouTube channel.

Imagine a cannon ball fired at such a high velocity that it could equal Earth’s gravitational pull. It’s going so fast that gravity can’t pull it back to Earth. It would continue to circle Earth — what we call an orbit.

If the cannon ball’s velocity were faster than Earth’s gravitational pull, it would leave orbit and head out into the solar system — which is how we launch probes out into deep space, and how Project Apollo sent astronauts to the moon.

The moon has its own mass, of course, so it also exerts a gravitational pull.

As a spacecraft travels from Earth to the moon, Earth’s influence becomes less and the moon’s influence becomes more. Velocity increases approaching the moon because its gravity is pulling the spacecraft towards it.

Here’s another thought experiment — what if the moon weren’t there?

Remember those terms apogee and perigee? If the moon didn’t exist, eventually our spacecraft would start to fall back to Earth, absent firing our engines or some other gravitational influence (such as the sun).

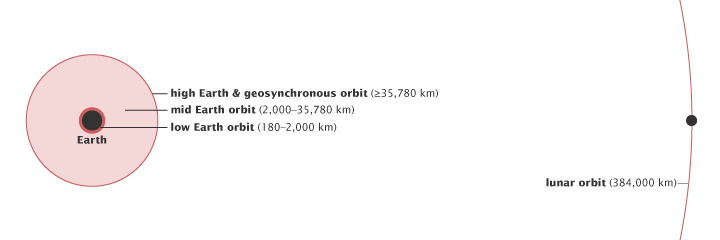

These days, most Earth-launched objects operate in our planet’s orbit. They’re anywhere from about 100 miles (160 km) to 22,000 miles (35,500 km).

An illustration of the three classes of Earth orbit. Image source: NASA.

As demonstrated by Newton’s Cannon Ball, for an object to orbit Earth it must equal the planet’s gravitational pull. The further away from Earth, the weaker the pull, so the object doesn’t have to go as fast as at lower altitudes.2

At 100 miles (161 km), the object would have to travel 17,474 mph (28,122 kph) to maintain orbit.

At 250 miles (402 km), the typical altitude of the International Space Station, the velocity would have to be 17,160 mph (27,616 kph).

Geostationary objects strive to stay over the same location at all times, such as a weather observation satellite. The math works out to an altitude of 22,236 miles (35,786 km). That’s so far away from Earth’s surface that the satellites travel at only 6,878 mph (11,070 kph).

This assumes a vacuum, which isn’t quite true. The ISS passes through a few wisps of Earth’s outer atmosphere. This creates drag, which requires the station to be boosted from time to time by visiting spacecraft such as a SpaceX Dragon or a Russian Progress cargo ship.

If you’re aboard the ISS, you experience microgravity3 because you’re in a spacecraft travelling at the velocity necessary to equal Earth’s gravitational pull.

NASA astronaut Jeff Williams demonstrates acceleration aboard the ISS during an orbital boost on January 24, 2010. Video source: NASA Johnson YouTube channel.

In the above video, any object (such as astronaut Jeff Williams or his camera) will accelerate during an orbital boost unless anchored to the space station.

So let’s go back to our original question — how can we make you float while on Earth?

Remember that to “float” you need to outrun Earth’s gravitational pull. We can do that for a short time by plunging an aircraft towards the surface. NASA, the European Space Agency, and Zero-G schedule such flights for microgravity training, science experiments, and adventure tourism.

ESA scientists perform microgravity experiments aboard a Zero-G aircraft. Video source: European Space Agency, ESA YouTube channel.

This trick works for about thirty seconds before the aircraft has to pull up. The microgravity scenes in the Apollo 13 movie were filmed aboard NASA’s KC-135 Stratotanker nicknamed the “Vomit Comet.” Each take could be no longer than 30 seconds.

For longer experiments, the ISS serves as humanity’s long-duration microgravity research laboratory.

But we still haven’t figured out how to turn off gravity on Earth.

Pop sci-fi such as Star Trek and Star Wars presumes the existence of artificial gravity, but never explains how gravity is created. If they can turn it on, presumably they can also turn it off.

The fictional spacecraft “Hermes” as seen in “The Martian” movie released in October 2015. Image source: The Martian Wikia.

More serious entertainment such as the 2015 film The Martian attempts to demonstrate a plausible means of creating artificial gravity. In that film, the spacecraft Hermes had a rotating segment to simulate gravitational pull.

On Earth, we can place you in a centrifuge to spin you and add gravity, but that won’t remove gravity.

About your only other option would be to book an adventure tourism flight aboard the Blue Origin New Shepard or a Virgin Galactic spaceplane. Those flights take you to an altitude of about 62 miles (100 km) where you experience about five minutes of microgravity before your spacecraft starts to fall back to Earth.

But we still don’t have a room where we can turn off gravity so you can float.

After “Where’s the bathroom?” and “Where’s the exit?” the most common non-logistical question was, “How do you go to the bathroom in space?”

The Earth Orbit Calculator at the Omni Calculator website is a handy place to calculate satellite velocities at a certain altitude. https://www.omnicalculator.com/physics/earth-orbit Have fun!

Technically, there’s no such thing as “zero gravity.” You experience gravitational pulls from every object in the universe, but it’s so miniscule as to have almost no effect on you at all. That’s why we use the word “microgravity.”

I have lately become interested in a medical phenomenon of which I am sure you are aware: Spaceflight‑Associated Neuro‑Ocular Syndrome (SANS).

It appears to arise from a set of interrelated disturbances in cranial and orbital fluid mechanics, venous hemodynamics, and tissue biomechanics produced by prolonged exposure to microgravity. No single unifying mechanism has been proven; current clinical and translational evidence supports a multifactorial model in which cephalad fluid shifts trigger downstream alterations in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) dynamics, translaminar pressure relationships, ocular interstitial fluid balance, and vascular structure/function. Individual anatomic and physiologic susceptibility factors modulate whether and how these primary perturbations produce optic nerve head edema, globe flattening, choroidal changes, and visual dysfunction.