The Cold War

Congress mandated in 2010 that NASA use liquid hydrogen as the fuel for its next heavy-lift rocket. Here's why.

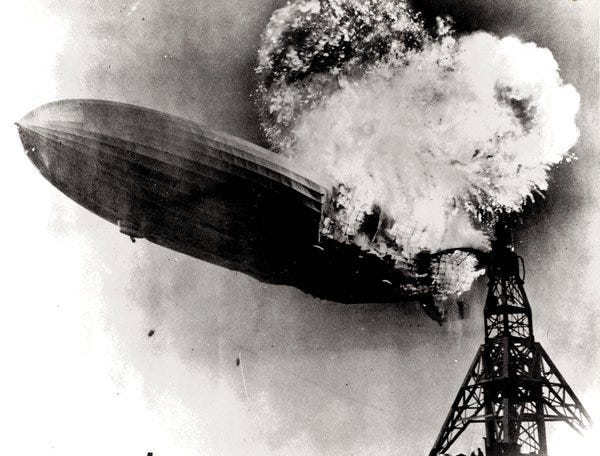

The Hindenburg used hydrogen gas to inflate its bladder. Hydrogen and oxygen don’t play well together when exposed to an ignition source. Image source: Caltech.

NASA conducted its first wet dress rehearsal (WDR) of the Artemis II launch stack earlier this week, at Kennedy Space Center’s Pad 39B. The mission hopes to send a crew of four to orbit the moon sometime this spring.

The WDR was less than perfect, as a liquid hydrogen (LH₂) leak in a Space Launch System core stage interface forced an end to the test with about five minutes left in the countdown.1

Although disappointing to some, the WDR went much better than Artemis I in November 2022, which had to roll back to the Vehicle Assembly Building three times that year due to LH₂ leaks.

At the post-WDR media event, NASA officials expressed confidence that this leak can be fixed on the launch pad with no roll back. They hope to conduct another WDR in time to launch sometime in March.

What is liquid hydrogen? Why is it used as a fuel? Why is it used if it’s prone to leaks? Are other options available?

What is Liquid Hydrogen?

Hydrogen, as you may recall from high school chemistry, is the lightest and most abundant element in the universe. Water is H₂O because it has two hydrogen atoms and one oxygen atom. Under the right conditions, hydrogen and oxygen get along fine.

Under the wrong conditions, it can go kaboom. An infamous example is the Hindenburg disaster on May 6, 1937. A spark ignited leaking gaseous hydrogen.

The Hindenburg could have used inert helium gas, but the Helium Act of 1925 banned the export of helium to protect US reserves. Other nations were forced to use the more hazardous hydrogen gas.

Hydrogen normally exists as a gas. To get hydrogen into a liquid state, it has to be reduced to a temperature of at least -423°F (-253°C).

Why would we want hydrogen in a liquid state?

One reason is storage. Liquid hydrogen is denser than when it’s a compressed gas. It gives you the best bang for the buck. To quote from the University of Michigan:

Hydrogen has the highest energy per mass of any fuel at 120 MJ/kg H₂ on a lower heating value basis, but very low volumetric energy density of 8 MJ/L for liquid hydrogen …

Simply put, LH₂ gives you a lot of energy but you need a very large tank to hold just a little of it.

Another reason to liquefy hydrogen is if you want to mix it with another liquid, such as liquid oxygen (LOX). To keep LOX in a liquid state, it must be at least -297°F (-183°C).

A propellant is a mixture of a fuel with an oxidizer.

Why Use Liquid Hydrogen as a Fuel?

The fire triangle. Image source: Wikipedia.

A rocket engine is pretty useless unless you give it something to burn.

The principle is the same as how you might light a fire in a fireplace. You need three ingredients:

Oxygen. The air you (and your fire) breathe is about 20% oxygen.

Heat. This might be a match or a lighter.

Fuel. You can use a log, newspapers, cardboard, anything that will burn.

This is known as the fire triangle. Without all three, you have no fire. Firefighters use water to put out a fire because it reduces the heat.

Let’s apply our fire triangle to rocket propulsion:

An oxidizer. LOX is the most common oxidizer, but any substance with the oxygen molecule might do.

An ignition source. TEA-TEB is a commonly used; it’s a liquid that ignites when exposed to air. (Look for a green flash in the exhaust at launch time.) Hypergolic propellants ignite spontaneously on contact with one another, so they don’t need an igniter.

That leaves fuel …

Ancient Chinese used a form of black powder. In more modern times, Russian mathematician Konstantin Tsiolkovsky in the early 20th century hypothesized the use of LOX and LH₂ as a propellant. In the 1920s, US physicist Robert Goddard used LOX and gasoline for his first rocket test in 1926.

After World War II, the US military began serious rocketry research. (So did the Soviet Union, the United Kingdom, and France.) Part of that research involved assessing the relative benefits of various fuels and oxidizers, both liquids and solids.

An excellent book on the topic is The Development of Propulsion Technology for US Space-Launch Vehicles, 1926-1991 by J.D. Hundley.2 I find the book fascinating, because it turns rocket history sideways. Instead of thinking about rocket lineage by agency — Army, Air Force, Navy, NASA — it views lineage by propellant.

Hundley helps us understand why LH₂ came into vogue. Chapter 5 is titled, “Propulsion with Liquid Hydrogen and Oxygen, 1954-91.”3 Von Braun’s German rocket team in the 1930s experimented with LH₂ but gave up on it due to leaks and the required large tank volume. Metallurgy needed to advance to make LH₂ practical.

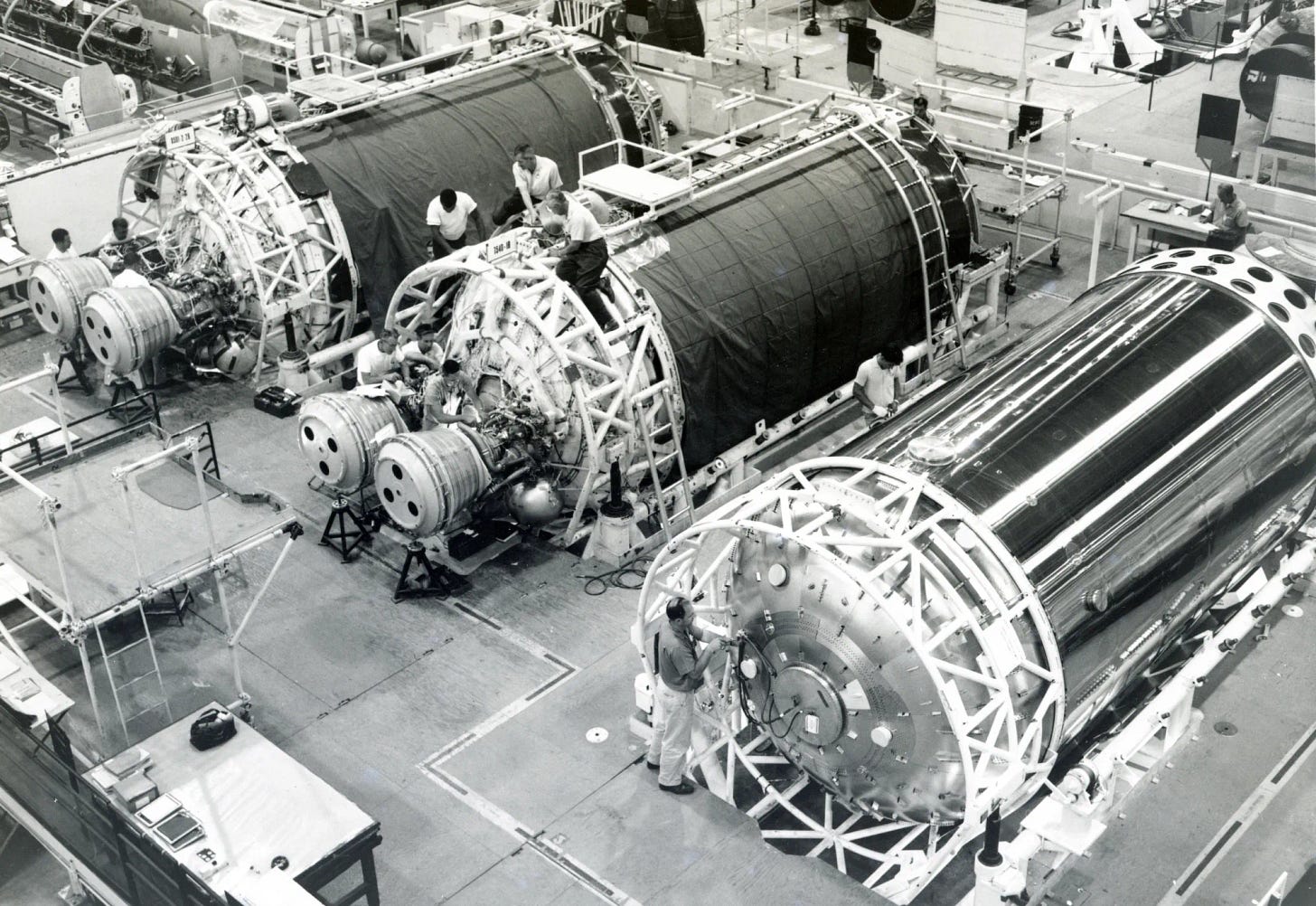

Centaur upper stages in 1963. Image source: NASA.

The first working LH₂-fueled space vehicle was the Centaur upper stage. Centaur was originally designed by General Dynamics’s Convair division to sit atop its Atlas booster. Upper stages don’t light at launch; they separate from the booster at a certain altitude, then light their own engine(s) to accelerate existing velocity and deploy a payload.

This addressed the tank volume issue. If the rocket is already in near-vacuum and travelling thousands of miles per hour, then a small LOX/LH₂ tank is practical. But Convair engineers also experienced leaks from microfractures in the bulkhead.

Why Use Liquid Hydrogen If It’s Prone to Leaks?

When President John F. Kennedy on May 25, 1961 proposed the crewed lunar program that eventually became Project Apollo, he knew that NASA had several research programs already underway developing engines for next-generation boosters. Each engine was designed for a specific propellant.

The Rocketdyne F-1 engine used RP-1 kerosene as a fuel.4 NASA selected the F-1 as the engine for the Saturn V rocket’s first stage. RP-1 was relatively safe. It could be stored at room temperature. It didn’t cause leaks. It didn’t require a large volume compared to LH₂.

After some debate, NASA selected LH₂ as the fuel for the upper stages to reduce weight. That meant a new engine, dubbed the J-2. LH₂ improved specific impulse by 40% compared to the F-1 engine fueled by RP-1.5 This forced the evolution of new aluminum alloys to withstand the extreme cold of LOX and LH₂.6

LH₂ leaks happened throughout Apollo. During the Apollo 11 countdown, a third stage replenishing valve leaked.7 Apollo 12 experienced a LH₂ fuel tank leak during its countdown.8

Despite the leaks, the United States emerged from the Apollo program as the lone nation with a mastery of liquid hydrogen as rocket fuel.

Once the Apollo program ended, the Nixon administration chose the Space Shuttle as NASA’s next crewed spaceflight program. The shuttle was pitched to the administration and Congress as an environmentally friendly reusable space transportation system.

As early as February 1970, nearly two years before Nixon approved the Shuttle program, NASA issued a request for proposals to study a Space Shuttle Main Engine (SSME) design using LOX and LH₂.9 The SSMEs were to burn a 6:1 ratio of LH₂ to LOX. This propellant mix appealed not only because of LH₂’s specific impulse but, if reusability was a goal, the engine exhaust would be superheated water vapor (H₂O!), therefore the engines should be much easier to clean than one burning a hydrocarbon such as RP-1.

Here’s the problem … Remember we said that LH₂ lacks density. It’s best suited for an upper stage ignited sometime after launch. As a first stage booster … it sucks.

The STS-27 launch on December 2, 1988. Image source: NASA.

In the above image, you can see the two solid rocket boosters (SRBs) on either side of the orange external tank. The ET holds the LOX and LH₂ that feed propellant to the SSMEs on the bottom of the shuttle orbiter. At launch time, the SRBs provide 72% of the thrust from liftoff until they separate two minutes after launch.10

The big orange tank held 47,000 gallons of LH₂ and 18,000 gallons of LOX that had to be pumped into it on the pad on launch day. The system proved to be rife with LH₂ leaks throughout the history of the shuttle program, contributing to its expense and inefficiency.11

Are Other Options Available?

Well … yes and no.

Commercial companies are developing heavy-lift vehicles capable of sending crew and payloads beyond Earth orbit. The primary contenders are the SpaceX Starship and Blue Origin New Glenn. Neither of these has flown people yet, but it’s only a matter of time before they fly crew.

The problem is Congress fifteen years ago gave NASA no choice but to use the Space Launch System (SLS) for crewed flight. The main reason was to protect Space Shuttle contractor jobs during the Great Recession as the shuttle program came to an end. Congress mandated that NASA had to use existing Shuttle contractors, hardware, and employees when possible. The RS-25 engines on the bottom of the SLS core stage are renovated shuttle-era SSMEs.

The Artemis II stack rolls onto Pad 39B, January 18, 2026. Image source: NASA.

The SLS core stage and its twin SRBs are basically stretched versions of the Shuttle stack. The core stage holds 537,000 gallons of LH₂ and 196,000 gallons of LOX.12

Lots more to leak. Lots more places to leak.

Starship uses liquid methane as a fuel. New Glenn uses liquefied natural gas. Both need to be cold (-260°F) to maintain a liquid state, but that’s warmer than LOX and much warmer than LH₂.

Liquid hydrogen leaks will continue to bedevil NASA so long as Congress forces the agency to use SLS as its launch vehicle.

A wet dress rehearsal is “a prelaunch test to fuel the rocket, designed to identify any issues and resolve them before attempting a launch.” It’s “wet” because actual fuel and propellant are loaded during the simulation. Rachel H. Kraft, “NASA Conducts Artemis II Fuel Test, Eyes March for Launch Opportunity,” NASA blog, February 3, 2026.

You can order the book through Texas A&M University Press or Amazon. You can also find copies on eBay.

Hundley, 173-221.

Depending on the source, RP-1 is an abbreviation for Rocket Propellant-1 or Refined Petroleum-1.

Roger E. Bilstein, Stages to Saturn (Washington, DC: NASA, 1980), 129. “Specific impulse” is a measurement of thrust relative to propellant weight.

Aluminum 2014 was used for the LOX and LH₂ tanks in the second and third stages. Bilstein, 165, 217.

"Center Employees Saw Eagle Crew Launch to History,” Spaceport News, Vol. 43 No. 14, July 16, 2004, 2.

Bilstein, 374.

Hunley, 205.

Robert Galvez et al, “The Space Shuttle,” The Space Shuttle and Its Operations, 56.

Ben Evans, “Summer of Discontent: 25 Years Since the Shuttle Hydrogen Leaks (Part 1),” AmericaSpace website, August 1, 2015. Evans, Part 2, August 2, 2015.

"Space Launch System Core Stage,” NASAFacts, 2018, 2.