Is NASA Obsolete?

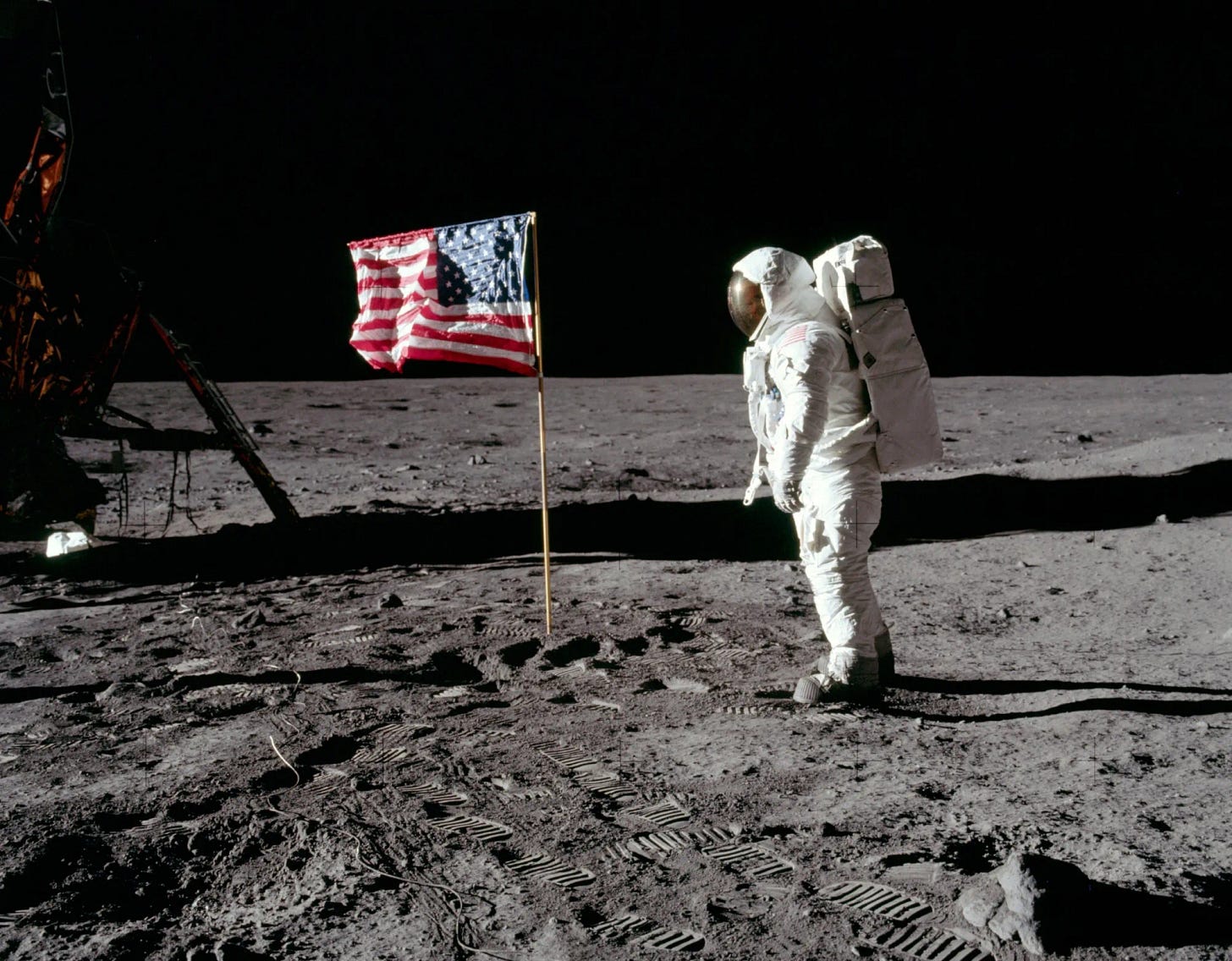

Project Apollo's crewed lunar program was a political response to the mistaken perception that Soviet space technology was superior to the United States.

Was this a mistake? Buzz Aldrin salutes the US flag after he and Neil Armstrong landed on the moon, July 20, 1969. Image source: NASA.

Fly Me to the Moon

Sometime this spring, it’s hoped, NASA will launch its Artemis II mission to the moon, from Kennedy Space Center here in Florida.

According to a May 2024 NASA Office of the Inspector General report, by the time Artemis II launches the agency will have spent more than $55 billion on the Space Launch System, Orion crew capsule, and associated ground systems to achieve that mission.

For what?

According to that OIG report, “With the Artemis campaign, NASA intends to return humans to the Moon and build a sustainable lunar presence as a foundation for human exploration of Mars.”

NASA’s website is a bit more expansive:

With NASA’s Artemis campaign, we are exploring the Moon for scientific discovery, technology advancement, and to learn how to live and work on another world as we prepare for human missions to Mars. We will collaborate with commercial and international partners and establish the first long-term presence on the Moon.

If you’re looking for a cost-benefit analysis, you won’t find one.

NASA took a stab at it. A thirteen-page report published in May 2022 cited the number of jobs created nationwide, the value of contracts signed, and estimated tax revenues generated. But it didn’t discuss what economic benefits will be derived from a permanent lunar presence.

More credible, in my opinion, was the argument that NASA restored the US space industry’s competitiveness in the global marketplace. But that wasn’t due to Project Artemis. It was due to a policy change begun during the George W. Bush administration, but taken seriously by the Barack Obama administration. NASA began using competitively bid fixed-price contracts to purchase space services off-the-shelf from the private sector. That predated Artemis.1

Governments typically don’t do cost-benefit analyses because they’re not driven by profit. Governments deliver a service. Your city hall doesn’t do a cost-benefit analysis to justify your police and fire departments. They’re on duty whether or not you need them.

So it is with Artemis.

Boots and Flags

“Landing of Columbus” by John Vanderlyn (1847) is on display in the US Capitol rotunda. Image source: Architect of the Capitol.

According to biographer Samuel Eliot Morison, when Christopher Columbus came ashore at San Salvador, he did so “in the armed ship’s boat with the royal standard displayed.”

It’s highly unlikely that San Salvador’s indigenous people comprehended the flag’s symbolic confiscation of their island but, in the more than 500 years since, the ritual has been for an explorer/conqueror to establish a claim by planting a flag.

The United States did so between 1969-1972 with its six crewed lunar landings. Unlike Spain, the US has never asserted rights to the moon. The 1967 Outer Space Treaty, which the US helped draft, specifically states that the moon and other celestial bodies are “not subject to national appropriation by claim of sovereignty, by means of use or occupation, or by any other means.” The plaque left by the two astronauts declared, “We came in peace for all mankind.”

This symbolism has come to be known as “boots and flags.”

Boots and flags have become a political justification for Project Artemis. When President Trump signed his Space Policy Directive-1 on December 11, 2017, he said, “This time, we will not only plant our flag and leave our footprints — we will establish a foundation for an eventual mission to Mars, and perhaps someday, to many worlds beyond.”

A return on taxpayer investment didn’t come up.

NASA began in 1958 as the successor to the National Advisory Committee on Aeronautics. The NACA was an independent institution conducting aviation research. Its findings were shared with other government agencies, academic institutions, and the private sector. The NACA was about science. Boots and flags were antithetical to its nature.

Project Apollo predated the Kennedy administration. It began in 1960 under President Dwight Eisenhower as a successor to Project Mercury, which was a one-person spacecraft. NASA envisioned Apollo as a three-person spacecraft that might be used some day for circumlunar flight.

My May 25, 2025 article “Kennedy’s Urgent National Need” detailed how Kennedy transformed NASA from an aerospace research-and-development agency into a tool of global soft power. His proposal essentially married Apollo to the Saturn rocket booster program. Saturn was also transferred to NASA in 1960, from the US Army, along with Wernher von Braun and his Huntsville, Alabama engineering team.

In his May 25, 1961 speech to Congress, Kennedy didn’t say what return the American taxpayer would enjoy from the expedition. What he did say was:

… [I]f we are to win the battle that is now going on around the world between freedom and tyranny, the dramatic achievements in space which occurred in recent weeks should have made clear to us all, as did the Sputnik in 1957, the impact of this adventure on the minds of men everywhere, who are attempting to make a determination of which road they should take.

NASA was no longer about science. It was now about prestige, one front in the Cold War with the Soviet Union.

The Rules of the Road

A December 4, 2025 House space subcommittee hearing to examine China’s threat of “becoming a dominant space power.” Click here to read the hearing charter. Video source: Space SPAN YouTube channel.

Many politicians these days justify Artemis by recycling the “space race” paranoia of the 1960s. If we don’t land on the moon first, the commies win. In the 1960s, the commies were the Soviet Union. In the 2020s, the commies are the People’s Republic of China.

When President Kennedy proposed his moon expedition, the Soviets had nothing similar. There was no lunar “space race” until the Soviets decided around 1964 or so to give it a go.2 By the time Apollo 11 landed on the moon in July 1969, the Soviets had already landed robots on the moon, but they had given up on a crewed mission, turning their efforts to the first crewed Earth-orbit space stations.3

As we enter 2026, China has yet to demonstrate the technology to send crew to the moon’s surface, and return them safely to Earth. They’re working on it. But you won’t find a Putonghua (Mandarin) language cost-benefit analysis either. Authoritarian regimes don’t have to justify how money is spent.

Even if China landed first, would it matter?

A November 2025 RAND report concludes:

A crewed Chinese lunar landing will carry profound symbolism, especially if the country gets there before NASA's planned return mission. But such a feat would go beyond simple prestige: “The countries that get there first will write the rules of the road for what we can do on the Moon,” former NASA Associate Administrator Mike Gold told a recent U.S. Senate hearing.

But the “rules” have been written, a long time ago. The United Nations created the Outer Space Treaty in 1967, negotiated primarily by the US and the USSR. Virtually all spacefaring nations have signed it, including the People’s Republic of China in 1984.

The UN’s Committee on the Peaceful Uses of Outer Space (COPUOS) is where the world goes to establish the space “rules.” You can read the rules at this link, including which countries have ratified which rules.

Not all the rules are respected. For example, the UN in 1979 passed what’s commonly called the Moon Agreement. Neither the US nor Russia nor China has ratified it. In 2020, President Trump issued an executive order rejecting the Moon Agreement:

… [T]he United States does not consider the Moon Agreement to be an effective or necessary instrument to guide nation states regarding the promotion of commercial participation in the long-term exploration, scientific discovery, and use of the Moon, Mars, or other celestial bodies.

NASA and the US State Department that year established the Artemis Accords as an alternative to the Moon Agreement. Fifty-nine nations have signed the accords. Russia and China have not.

So rules do exist. The question is if the rules will be honored.

If China lands in a crater and claims it owns the moon, so what? No other nation will honor the claim. The Artemis partners can land in another crater and claim it as theirs. China won’t be able to do anything about it.

The more likely scenario is that, sometime later this century, commercial enterprises will stake claims to finite lunar resources such as frozen water. COPUOS is working on this and other issues.

But we still haven’t answered the cost-benefit question. Is there a commercial return on Artemis? Or is it really all about boots and flags?

Cash on Delivery

The Columbus expedition of 1492 is portrayed in the history books as boots and flags. To some extent, that’s true.

But a better analogy might be today’s NASA commercial crew and cargo programs.

NASA fixed-price contracts for ISS deliveries trace back to the George W. Bush administration, which opened the Commercial Crew & Cargo Project Office (yes, C3PO) in November 2005. The concept was to transfer delivery services to the private sector, with limited government investment. The private sector, not the government, would own the vehicles, the patents, and the workforce. The government’s role was to assume some of the risk by providing milestone payments to the competing contractors.4

That’s how the Columbus voyage worked.5

Convinced that Earth is round and that he could navigate trade winds west, Columbus approached European monarchies seeking a ruler who might appropriate royal funds for financing an expedition. Trade with India and China was either by land, or by sailing around Africa’s Cape of Good Hope to Asia. Columbus claimed that a sponsoring nation would have a shorter trade route as well as claim of any undiscovered lands he found.

It wasn’t smooth sailing, so to speak. Columbus waited for years to get an audience with Queen Isabella. The monarchy agreed to partially finance the expedition, but the rest was funded by money Columbus borrowed. The three ships were privateers. Their crews were private as well.

Keep in mind that, just like today’s commercial programs, Columbus didn’t get paid unless he delivered. He could appoint himself Viceroy and Governor-General over any lands he discovered. He could keep a tenth of the riches he obtained from these domains, tax free. If he failed to deliver? If he failed to return? He received nothing.

The Spanish monarchy assumed a modest risk for the potential of not just collecting treasures but also a strategic advantage over its rival powers. That was the return on its investment, not boots and flags.

What Should NASA Be?

Since the time of Apollo, NASA’s spacecraft and launch vehicles have been built by private companies signed to cost-plus contracts. The companies are guaranteed a profit. The government owns the spacecraft but assumes all the risk. If the company fails to deliver on time or at cost, the taxpayer absorbs the loss.

This socialistic business model is an anachronism. It runs contrary to centuries of exploration, which rewarded results.

In my opinion, it’s time for NASA to revert to what it was intended to be.

I’m under no illusion that this will happen. Congress likes the socialistic model just fine. The Artemis Space Launch System was built at congressional directive by legacy aerospace companies awarded no-bid contracts. That’s why some call SLS the Senate Launch System.

But if I had a magic wand to wave, here’s what I would do.

NASA’s full name is the National Aeronautics and Space Administration. The aeronautics part came from the old NACA. That was at a time when it was unsure how best to reach space — by a rocket or by a plane.

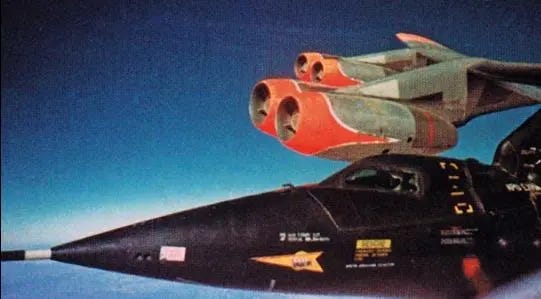

The X-15 was taken aloft under the wing of a B-52. After release, its engines lit like a rocket to propel it to high altitudes. Image source: NASA.

Horizontally launched orbital rocketry for now seems to be an evolutionary dead-end. So is there still a reason for NASA to do both aviation and space?

I’d divorce the two. Resurrect the NACA and let that agency focus on aeronautics. The rest would become the new NASA — National Aerospace Science Administration.

Aviation is a mature industry with more than a hundred years of experience. Space? About half of that. We still have much to learn. By the end of the 1930s, commercial passenger aviation was common for the wealthy. Only now are we seeing commercial space travel — again, by the wealthy.

NASA 2.0 needs to be what NACA 1.0 had become by the mid-1930s — an “internationally known and respected” aviation research agency. When war broke out after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, the NACA’s pioneering research helped US industry develop new aircraft such as naval dive bombers. Its research database led to low-drag wings, high-speed propellers, and improved cowling and cooling systems.6

In a 1969 interview with Syracuse University participants, Kennedy’s NASA administrator James Webb said that his management team viewed the end-of-decade goal as a “political forward thrust” that justified their building “all elements of a total space competence.”7

… [W]e had to develop all of the capabilities required for a great nation to insure its destiny. So the lunar project to us was little more than a realistic requirement for space competence as well as a way of developing the kind of capabilities that were total.

A half-century later, the US has that space competence, but it’s held back by how Congress does business.

So let’s begin with the return-on-investment discussion.

Commercial companies make lots of money now in low Earth orbit, by communication systems such as Starlink and Earth observation constellations such as Planet.

With the advent of artificial intelligence systems and their requirements for vast energy, there’s talk of moving data centers off-world where they can use solar power. Starcloud is one company investing in the idea. Space data centers would be a great place for NASA to partner with the private sector.

As humanity establishes a permanent commercial presence in low Earth orbit, logically we’ll expand out into the solar system. That means humans in space — not for boots and flags, but for commercial enterprise. Commercial space stations such as Axiom Space should be operational circa 2030. The International Space Station has taught us how humans can live off-world for over a year. It’s time to let go and transfer that technology to the private sector.

When Columbus crossed the Atlantic, when Lewis and Clark explored the Louisiana Purchase, robotics didn’t exist. They do now. Boots and flags require risking a human life. Nations have been landing robots on the moon since the 1960s. The US, the Soviet Union, and China have landed robots on Mars.

Those expeditions were in the name of science. So far, they’ve returned no hard evidence that either world has resources justifying the risk and expense of sending people. Sure, the moon has mineral resources that are finite here on Earth. But it would be hideously expensive to mine those minerals on the moon and return them here. The cost would be too high for the benefit.

Some have argued that helium-3 might be abundant in the lunar regolith. Helium-3 could be used to power fusion reactors. But fusion reactors are still in the experimental stage here on Earth, and have yet to be proven commercially viable. Even so, let’s get back to the cost-benefit analysis — how much would it cost to permanently staff a crewed lunar base and operate equipment necessary to harvest helium-3 and send it back to Earth? That answer is too far in the future to justify crewed lunar bases now.8

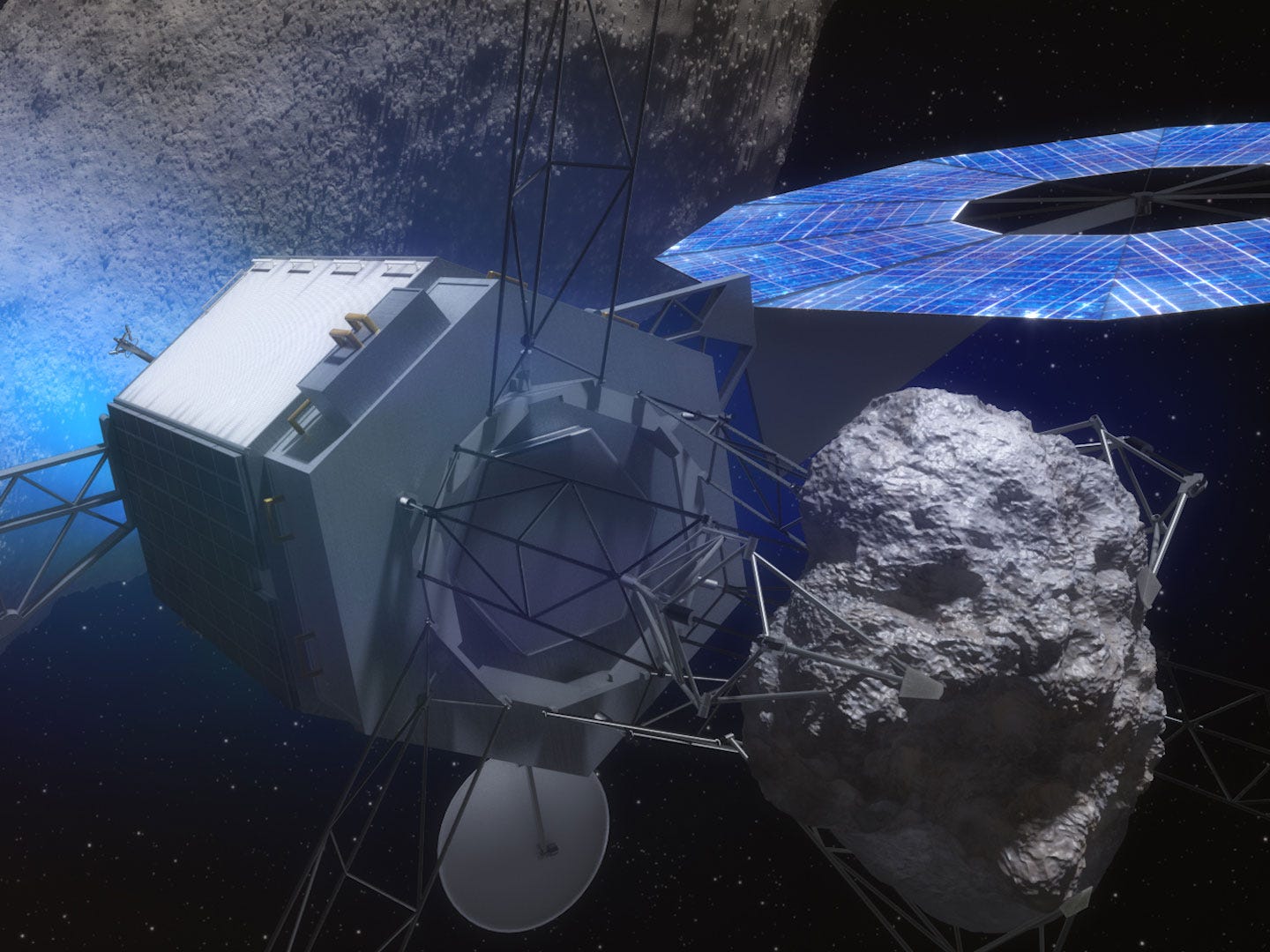

More justifiable, and with less risk, would be bringing asteroids to Earth orbit where they could be harvested. The Obama administration proposed the Asteroid Redirect Mission, which would have pioneered the technology for such an endeavor, but it was unpopular with Congress. The Trump administration killed ARM in 2017.

The Asteroid Redirect Mission as envisioned by NASA. Image source: NASA/JPL.

A new ARM program would be a great opportunity for artificial intelligence companies to demonstrate how their technologies could perform the tasks envisioned a decade ago for astronauts.

As these “space mines” are established, “towns” should pop up nearby. Much closer to Earth, NASA could support commercial enterprise by acting as an angel investor for these way stations. Step by step, humanity would expand out into cislunar space, evolving and maturing technologies as the NACA did nearly a century ago with airplane technology. Boots may not be stomped, flags may not be waved, but the endeavor would be sustainable.

What happens to pure science? Good question. But science is already endangered now. The Mars Sample Return mission is all but dead. The Perseverance rover has been collecting samples, but Trump and Congress have no interest in paying for a mission to bring them back. Trump’s Fiscal Year 2026 budget cut NASA science funding by 75%. Congress may restore much of it, but it’s not a done deal, and the FY27 budget proposal may try to cut it again.

Billionaire Eric Schmidt has offered to finance four space telescopes, which would be in the tradition of how many ground-based telescopes were built a century ago. Businessman Percival Lowell built his Flagstaff, Arizona observatory in 1894. That’s where Pluto was discovered in 1930. Philanthropist Griffith J. Griffith donated the money to build the Griffith Observatory in Los Angeles. A Rockefeller Foundation gift to Caltech financed the Palomar Observatory in San Diego County.

Since we can’t rely on a president or Congress to support science, we need to find ways to encourage philanthropists to fund science. NASA can offer to partner, perhaps even be a primary tenant.

What happens to existing NASA centers? Many facilities are obsolete or even shuttered.

Florida has shown the way. Space Florida is a state non-profit that partners with the government and private sector to find new uses for old facilities. They’re responsible for SpaceX and Launch Complex 40 and LC-39A, Blue Origin at LC-36, Boeing in the former Shuttle maintenance hangars, and much more.

Some states have an equivalent. Virginia has the Virginia Spaceport Authority. Coastal California communities near Vandenberg Space Force Base created the Regional Economic Action Coalition. Texas founded the Texas Space Commission in 2024.

Just as obsolete military bases have closed and found commercial use, so it should be with NASA centers. Where state and/or regional authorities don’t exist, NASA should encourage their creation. Failure to do so could leave locals with abandoned government facilities and no jobs.

The Obama administration attempted these reforms in 2010, but encountered fierce bipartisan resistance from both houses of Congress. History has proven that Obama, NASA deputy administrator Lori Garver, and other reformers were right. Those who resisted were on the wrong side of history.

Time to right a wrong.

The George W. Bush administration opened the Commercial Crew/Cargo Project Office on November 7, 2005. Congress questioned the use of Space Act Agreement contracts by the Obama administration to circumvent cost-plus contracts, which guaranteed a profit to the contractor regardless of performance.

Soviet space historian Asif A. Siddiqi discusses the Soviet decision at length in Challenge to Apollo: The Soviet Union and the Space Race, 1945-1974, Volume 1 (Washington, DC: NASA, 2000), “The Decision to Go to the Moon,” 395 et seq.

Luna-9 landed on the moon on January 31, 1966. The first US lunar lander was Surveyor-1 on June 2, 1966. Luna-16 landed on the moon on September 20, 1970, retrieved a small sample and returned to Earth. Lunakhod-1 landed on November 17, 1970; it was the first robotic rover on the moon. According to Asif Siddiqi, after Apollo 8 orbited the moon in December 1968 the Soviets shifted focus starting in January 1969 to develop Earth-orbital stations. Siddiqi, Challenge to Apollo, Volume 2, 675-678.

Rebecca Hackler, Commercial Orbital Transportation Services: A New Era in Spaceflight, NASA/SP-2014-617.

Morison, 96-104.

J.C. Hunsaker, “Forty Years of Aeronautical Research,” Forty-Fourth Annual Report of the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (Washington, DC: US Government Printing Office, 1959), 21, 25, https://digital.library.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metadc64173/m2/1/high_res_d/20050019296.pdf.

H. George Frederickson, Henry J. Anna, and Barry Kelmachter, “Interview with Mr. James E. Webb,” Syracuse/NASA Program Project Manager Research Group, May 15, 1969, 22. A PDF of the interview was provided by the NASA Program History Office, but it’s not online.

Loura Hall, “Harnessing Power from the Moon,” NASA, June 19, 2015.