The Muskian Bargain

Elon Musk once sued to break ULA's launch monopoly. Twenty years later, the US government is nearly as dependent on SpaceX as it once was on ULA.

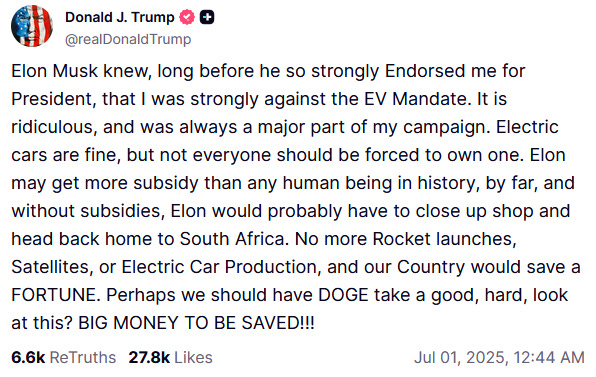

President Donald Trump, in the wee hours this morning, once again attacked the man who last year spent $288 million to elect him and other Republican candidates. Image source: Truth Social.

The soap opera starring Elon Musk and Donald Trump is bubbling yet again.

Musk left his White House special advisor role on May 28. The political gossip was that Musk’s welcome had worn thin after offending Trump’s cabinet secretaries and White House staff.

After he left, Musk began criticizing the Trump budget legislation called “The Big Beautiful Bill” by the president. Trump in private allegedly called Musk “a big-time drug addict.” In public, Trump called for Musk’s government contracts to be reviewed.

Mediators arranged a ceasefire between the two thin-skinned egos. The ceasefire seemed to hold until this last weekend, when Musk once again began criticizing the budget bill. Musk yesterday threatened to spend his fortune on primary challenges against any Republican supporting the bill. Trump this morning accused Musk of receiving massive government subsidies (spoiler … look up the definition of a subsidy; contracts are not subsidies) and once again implied he might pull the plug on SpaceX government contracts.

Any such threats are empty. The US government, military and civilian, relies on SpaceX not only for crew and cargo deliveries to the International Space Station, but also for launching probes and satellites. The military uses SpaceX for launching its spy satellites as well as the X-37B spaceplane. To drive home the point, Musk threatened to decommission the SpaceX crew Dragon so astronauts could not travel to and from the ISS. With the Boeing Starliner years behind schedule, the only other viable option is purchasing rides on the Russian Soyuz. Purchases must be made years in advance so the capsules can be built, flight suits fitted, and custom seats made. That’s overlooking the strained relations between the US and Russia due to the Ukraine war.

As of this writing, the Senate just passed its version of the bill. It now goes to reconciliation with the House version. Reconciliation committees often take forever as compromises are sought; it wouldn’t be unusual for continuing resolutions to be passed as the new fiscal year approaches on October 1, to keep the federal government from shutting down.

Our interest here is not the budget bill, but to look at how Elon Musk and SpaceX became major players in the US government launch programs, both civilian and military.

A Legal Monopoly

The first SpaceX rocket, the Falcon 1, was still vaporware when Boeing and Lockheed Martin formed a joint venture in May 2005 called United Launch Alliance (ULA). Neither company could attract enough government or commercial launch business to remain financially viable. The Federal Trade Commission allowed the deal to go through, although it acknowledged “the loss of non-price competition and the loss of future price competition” as a result.

SpaceX filed a lawsuit in October 2005 challenging the creation of ULA. The FTC rejected the complaint, noting that SpaceX had no launch vehicle ready in the foreseeable future to offer the services provided by the Delta IV or Atlas V. The lawsuit was dismissed by a US District Court, citing the same reasoning.

It was around this time that President George W. Bush announced his Vision for Space Exploration. A June 2004 report by an implementing commission included a chapter titled, “Building a Robust Space Industry.” The authors declared:

The Commission finds that sustaining the long-term exploration of the solar system requires a robust space industry that will contribute to national economic growth, produce new products through the creation of new knowledge, and lead the world in invention and innovation. This space industry will become a national treasure.

The commission recommended that, “ NASA aggressively use its contractual authority to reach broadly into the commercial and nonprofit communities to bring the best ideas, technologies, and management tools into the accomplishment of exploration goals.”

On November 7, 2005, NASA opened the Commercial Crew/Cargo Project Office (C3PO, a nod to a certain Star Wars protocol droid). NASA administrator Michael Griffin told Congress that the agency would solicit the private sector to demonstrate space delivery services; if successful, they would have the chance to bid for fixed-price NASA contracts — unlike the cost-plus contracts enjoyed by NASA and military launch service companies for decades that guaranteed a profit regardless of performance or cost.

Griffin was an aerospace engineer and executive who, by happenstance, was on Musk’s flight to Moscow in 2002 when Musk tried to acquire a Russian ICBM to send a greenhouse to Mars. Russia said no; it was that denial that provoked Musk into creating SpaceX.

Elon Musk meets with newly appointed NASA administrator Michael Griffin on April 20, 2005. Image source: DVIDS.

In August 2006, NASA announced that two companies had been awarded commercial cargo contracts — Rocketplane Kistler (RpK) and SpaceX. Unlike the cost-plus contracts enjoyed by Boeing and Lockheed Martin, these companies had to spend their own money to develop their launch technologies. If they achieved their milestones, NASA gave them an award, and they moved on to the next milestone. If they failed — they were out.

RpK failed its fourth milestone — adequate funding — and was terminated in October 2007. It was replaced by Orbital Sciences, which received the balance of the funding budgeted for RpK.

None of these companies received “subsidies.” They were required to invest their own money in exchange for a milestone payment. If a milestone could not be achieved, the company was out its own investment and did not receive its milestone award. The company would not have the opportunity to bid for a NASA fixed-price contract.

Years later, Elon Musk in 2015 would allege that ULA received $1 billion a year in subsidies from the US Air Force. ULA CEO Tory Bruno at the time described the “subsidy” as a prepayment for anticipated launch costs. SpaceX enjoys no equivalent prepayment.

Goliath, Meet David

By 2014, any launch company not named United Launch Alliance had a fighting chance.

The President Barack Obama administration, starting in 2010, expanded on the commercial cargo program, using that model to start a commercial crew competition. Congress underfunded commercial crew for years, setting back the program to the end of the 2010s decade.

Several companies entered the competition — Boeing, Sierra Nevada, Blue Origin, ATK, Excalibur Almaz, and of course SpaceX. ULA was indirectly part of the competition, as its Atlas V was proposed as the launch vehicle for the Boeing Starliner.

The Atlas V, though, had a political problem. Its RD-180 engines were built by a Russian company called NPO Energomash. General Dynamics in the early 1990s had acquired the rights to use RD-180 engines in an Atlas rocket. The RD-180 was considered a cheaper alternative to US-built engines, and in the immediate post-Cold War era US-Russian business partnerships were encouraged to help Russia keep its aerospace engineers employed, lest they defect to a hostile nation such as Iran or North Korea. General Dynamics’ space technologies were acquired by Lockheed Martin in 1997, and with that the rights to the RD-180.

The Russian engine has proven quite reliable. The only known RD-180 failure was a lone engine during a 2018 launch, but it did not affect the payload delivery.

The problem was that in early 2014 Vladimir Putin directed Russia to invade Crimea, part of Ukraine. Shortly after this, the Pentagon gave ULA a 36-core block buy for national security launches, without allowing a competing bid. The US Air Force had certified ULA as the only company capable of making national security launches. SpaceX had applied for certification, but the Pentagon hadn’t completed that process before awarding ULA another monopolistic contract.

On March 5, 2014, Musk and ULA CEO Michael Gass were part of a panel testifying before the US Senate Appropriations Subcommittee on Defense. Musk hammered on Gass, noting that SpaceX engines were made in the US while Atlas V engines were made in the country that just invaded Crimea.

March 5, 2014 … The battle of the CEOs. Elon Musk and Michael Gass testify before a Senate defense subcommittee. Video source: Space SPAN YouTube channel.

In August 2014, Gass retired from ULA. Although publicly denied, the open speculation was that Gass’s performance before the subcommittee played a role in his demise. He was replaced by Tory Bruno, who remains CEO to this day.

In April 2014, SpaceX filed suit for the right to compete the contract. The lawsuit was settled in January 2015, with the USAF agreeing to expedite SpaceX certification while also making more launches available for competitive bid.

The commercial crew competition ended in September 2014 with SpaceX and Boeing winning fixed-price contracts. Boeing received $4.2 billion, but SpaceX only $2.6 billion. NASA never explained why Boeing received so much more, other than the agency accepted what the bidders requested.

In the nearly eleven years since then, SpaceX has flown ten operational crew delivery missions to the ISS, as well as four commercial missions for Axiom Space, two private crews purchased by billionaire Jared Isaacman, and one purchased by entrepreneur Chun Wang.

Boeing has flown only one crewed flight test with two NASA astronauts that is largely considered a failure. The Crew Flight Test in June 2024 experienced thruster anomalies. Although the astronauts reached the ISS, NASA finally decided to bring them home on a SpaceX crew Dragon.

Over the last ten years, SpaceX has achieved one significant aerospace first after another. On December 21, 2015, SpaceX successfully landed a Falcon 9. On March 30, 2017, SpaceX launched its first previously flown Falcon 9. As of this writing, SpaceX has successfully landed a Falcon 9 470 times — 380 on a drone ship at sea, and 90 on land.

On February 6, 2018, SpaceX launched the first Falcon Heavy — a center core with two used Falcon 9s strapped to its sides. Falcon Heavy launches are relatively uncommon, with eleven through 2024, but it should be noted that both the Falcon 9 and Falcon Heavy were developed and operated without the alleged government “subsidies.” The customer paid for the delivery service, no different than how we pay the US Postal Service, UPS, or FedEx to deliver a package. Those are business transactions, not subsidies.

Big for Their Britches

In recent years, SpaceX has won a number of Pentagon contracts. Where ULA once dominated, now it’s SpaceX. ULA has retired its other rocket, the Delta IV. An Atlas V successor called Vulcan has flown twice, with a third launch planned for July — a demonstration navigation satellite for the US Space Force.

In April, the US Space Force awarded SpaceX $5.9 billion for 28 future missions, $5.4 to ULA for 19 missions, and $2.4 billion to Blue Origin for seven launches. That’s an average of $210 million per launch for SpaceX, $284 million for ULA, and $343 million for Blue. Those numbers can be somewhat misleading, depending on the launch vehicle for the contracted missions, but still it suggests that SpaceX is the best price out there.

You probably know that Elon Musk envisions colonizing Mars with his Starship launch vehicles. Starship tests have not gone well, but again those are privately funded tests, not subsidies. SpaceX is one of two companies contracted by NASA to develop lunar landers for Project Artemis (Blue Origin is the other), but again these aren’t subsidies. The SpaceX lander is a Starship variant called the Human Landing System. As with commercial cargo and crew, these are fixed-price contracts with payments made only after milestones are achieved.

To fund his Mars dreams, Musk created a SpaceX division called Starlink. The satellite constellation provides high-speed Internet access around the world. It has proven so versatile that it’s invaluable for first responders to natural disasters, such as Florida’s Hurricane Ian in 2022. The Pentagon plans to acquire a military variant called Starshield that it would operate, not SpaceX.

SpaceX now permeates the US government, with good reason. But the consequence is that Elon Musk now has an outsized presence in government operations — and he knows it.

Musk’s stability has always been dubious at best. His eccentricities were documented by Ashlee Vance in his 2015 Elon Musk biography. Since then, Musk has been prone to explosions of temper. One example is his 2018 outlash calling a British cave diver “pedo guy” after the man criticized a mini-sub Musk was having SpaceX build for a Thailand rescue attempt. Although the charge was baseless, a Los Angeles jury in December 2019 found that Musk did not defame the man.

After Russia launched its full invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, Ukraine found Starlinks to be invaluable in the field. But when the Ukraine government asked to use Starlink to launch an attack on Russian naval vessels in Sevastopol, Musk said no. Perhaps he feared Russia might attack his satellite network, who knows. But he’d established the precedent that he could insert himself into military operations. In March 2025, after a fallout between Trump and Ukraine president Volodymyr Zelenskyy, Musk assured that Ukraine could keep its Starlink systems even if Trump cut off aid to the invaded nation.

In April 2024, Musk fired his entire Tesla supercharger division in anger after a presentation by his Senior Director of Charging Infrastructure, Rebecca Tinucci. Many of them eventually were rehired, but Tinucci moved on to Uber.

A year later, after Musk’s behavior on Trump’s campaign trail and in the White House, The Wall Street Journal reported that the Tesla board of directors was looking for a new CEO. Musk and Tesla denied the report, but shortly thereafter it was announced that Musk would soon leave the administration to return to running his businesses.

May 30, 2025 … Donald Trump and Elon Musk say farewell in the Oval Office. They began their social media spat shortly thereafter. Video source: News from the Past YouTube channel.

Within hours after Musk’s Oval Office farewell, Trump fired his own NASA administrator nominee. Jared Isaacman, a billionaire philanthropist who has flown twice on private SpaceX crew missions, was recommended by Musk. It appeared to be retaliation for Musk’s verbal abuses of White House staff.

Since then, Musk and Trump have warred in social media. Musk has threatened to cut off government services that his companies provide, while Trump has threatened to terminate those companies’ contracts and non-existent “subsidies.” Neither will happen, of course, because both the US government and Musk companies have too much at stake.

What Goes Around …

So here we are, twenty years after the US government said it was okay for ULA to create a legal monopoly in commercial launch services. The company that sued to stop it and lost now has its own de facto monopoly. Unlike with ULA, the SpaceX monopoly was unintended, but nonetheless it exists.

What to do about it?

The answer, now as it was back then, is to encourage competition. The problem is that no company has yet to show it can compete. SpaceX arguably has in its employ the brightest and most talented space engineers in the industry. Most of them are young and energetic, motivated by Musk’s vision of interplanetary travel. They are conjuring the future.

No other company can so inspire.

But some of that talent moves on as Musk burns them out. The recent Starship failures could be evidence of a brain drain, but that’s strictly my speculation.

It took twenty years to build the SpaceX monopoly. It may take that long to unwind it.