Talk is Cheap

New NASA administrator Jared Isaacman promises the moon and more, but doesn't say how to pay for it. That's the same failed recipe that's doomed NASA for a half-century.

Jared Isaacman conducts a town hall with NASA civil service employees on December 19, 2025. Video source: Space SPAN YouTube channel.

When we last discussed him in late May, Jared Isaacman had just been sacked by Donald Trump. The impulsive president had just withdrawn Isaacman as his nominee for NASA administrator, even though Isaacman already had his Senate confirmation hearing on April 9, and was expected to be approved by bipartisan vote when his name reached the Senate floor sometime in June.

But the White House notified the Senate on June 2 that Trump had withdrawn the nomination. According to a December 29, 2025 Washington Post article, Isaacman was collateral damage from the president’s feud with Elon Musk, who had recommended his fellow billionaire for the job.

Palace Intrigue

On Musk’s last day, White House aide Sergio Gor placed before Trump a document showing that Isaacman had made campaign contributions to Democrats. That should have been no surprise to anyone; public records available on the Open Secrets website show Isaacman has donated to both Democrats and Republicans.

According to the Post, Gor was one of a “roster of adversaries” Musk had within the White House. Gor’s payback was to sabotage Isaacman’s nomination.

Within days after Isaacman’s dismissal, Musk began attacking Trump’s budget bill in public. The two feuded in social media. Trump threatened to cancel SpaceX contracts. Musk responded by theatening to create his own political party.

The Post reports that Vice President JD Vance reached out to Musk, hoping to stop him from spending billions on a third party that could siphon off Republican MAGA voters. According to the Post:

Vance and others knew that a top priority for Musk was the confirmation of his friend Isaacman as NASA administrator. Vance pushed for Isaacman to have the position again, speaking with relevant members on the Senate Commerce Committee to make sure he had the support he needed and would receive a quick confirmation.

By coincidence or not, in late August Trump nominated Gor to be US ambassador to India. The Wall Street Journal reported on August 22:

Mr. Gor was valued by the president for his perceived loyalty, and his willingness to freeze out of government people he considered insufficiently pure in that regard. But he was also criticized by others as capricious in how he made those decisions. And he fought bitterly with Elon Musk, Mr. Trump’s billionaire adviser who ran an effort that ripped through existing government systems in the name of cutting costs and who himself often fought with others in the government.

The article reported that Trump was unhappy with Gor after learning that the aide misled him about Isaacman.

In any case, NASA remained rudderless for months. Transportation secretary Sean Duffy took on the additional responsibility of running NASA while the White House slashed NASA’s budget. Trump’s Fiscal Year 2026 NASA budget proposed to cut the agency’s funding from $24.8 billion to $18.8 billion ($6.0 billion or 24.2% from FY25).

By October, media reports surfaced that Duffy wanted the job permanently, and wanted to fold NASA into his Department of Transporation. But the rumor mill also had Isaacman back in Trump’s good graces.

On November 6, the White House announced that Isaacman had been nominated again. A second nomination hearing was held on December 3.

Jared Isaacman’s second nomination hearing, on December 3, 2025. Video source: Space SPAN YouTube channel.

Two weeks later, on December 17, the Senate approved Isaacman 67-30. The next day, Isaacman was sworn in as NASA’s fifteenth administrator.

This Sounds Familiar

Coinciding with that event was the release of an executive order by the White House portrayed by Isaacman and others as a new US national space policy.

One could quibble whether or not this really is a new “space policy.” It doesn’t call itself a national space policy. Much of it amends or supercedes policies issued by George W. Bush, Barack Obama, Trump during his first administration, and Joe Biden.

The Center for Space Policy and Strategy maintains a website listing space policy archives going back to Harry Truman. Click here to view the documents. You can decide for yourself how much of this new policy is just a rehash of prior declarations.

Any “policy” released by the White House, to be honest, doesn’t mean much. Congress decides what NASA (and every other federal agency) does, and how much funding they’re appropriated. Trump’s policy can say, “NASA will send astronauts to Vulcan in 2028” but, if Congress says no, it doesn’t happen.

Esther Brimmer of the Council on Foreign Relations commented:

The executive order removes earlier policy directives. While it authorizes a new space policy, the order also dismantles elements of previous policy mechanisms, including the National Space Council that was originally launched at the end of the first Trump administration. The new policy enhances the role of the Commerce Department in acquisition and prioritizes solutions from commercial entities.

Brimmer noted that Trump’s budget cut NASA’s science budget by 47%. She wrote:

Gutting of science funding and undermining the independence of universities erodes the ecosystem that has helped create U.S. leadership in space. The new space policy offers a chance for a revitalized approach to U.S. leadership in this vital domain.

Therein lies the problem.

Isaacman, so far, has given no indication that he will seek to restore NASA’s funding, nor does he explain how he might replace lost programs.

Trump’s new policy sets as an objective a crewed lunar landing by 2028. As recently as October, NASA projected Artemis III for mid-2027. So 2028 is a backslide, most likely an acknowledgement that neither Human Landing System contractor — SpaceX or Blue Origin — will be ready with their system in time.

Perhaps the most significant, and perhaps the most obscure, revision is investing power in the Assistant to the President for Science and Technology (APST). That person is currently Michael Kratsios, who served as Chief Technology Officer during Trump’s first term. He joined the second Trump administration after serving as managing director at Scale AI, a generative artificial intelligence company.

The APST replaces the National Space Council, an advisory body that traces back to NASA’s origin in 1958. Some presidents have staffed it. Some have not. The Obama administration didn’t use the council, but Trump and Biden did.

Politico reported in July 2025 that the second Trump administration was trying to staff the council but couldn’t find anyone. Apparently this policy is an acknowledgement that the council may be obsolete, or it could reflect Trump’s preference to consolidate power in loyalists who will do his bidding without debate.

This seems to be what Jared Isaacman is trying to demonstrate.

Hail to the Chief

Isaacman has granted several interviews since taking office. Many times, he’s bordered on the obsequious, lavishing undeserved praise on Trump.

Typical is this December 18, 2025 interview with CBS News correspondent Major Garrett.

December 18, 2025 … Jared Isaacman credits Donald Trump with NASA policies and programs that began under other administrations. Video source: CBS News YouTube channel.

I also think it’s about fulfilling a promise for more than 35 years that presidents have said we’re going to return to the moon and chart a course for Mars, but really it was only under President Trump in his first term that he returned American spaceflight capability to the United States. We spent a decade paying the Russians to send our astronauts to space until President Trump. He kicked off the Artemis program, and now he’s taking it a step further with this national space policy, again, committing us back to the moon, setting up the infrastructure, and then going beyond.

Let’s begin with the claim that Trump “returned American spaceflight capability.”

That was actually President Barack Obama.

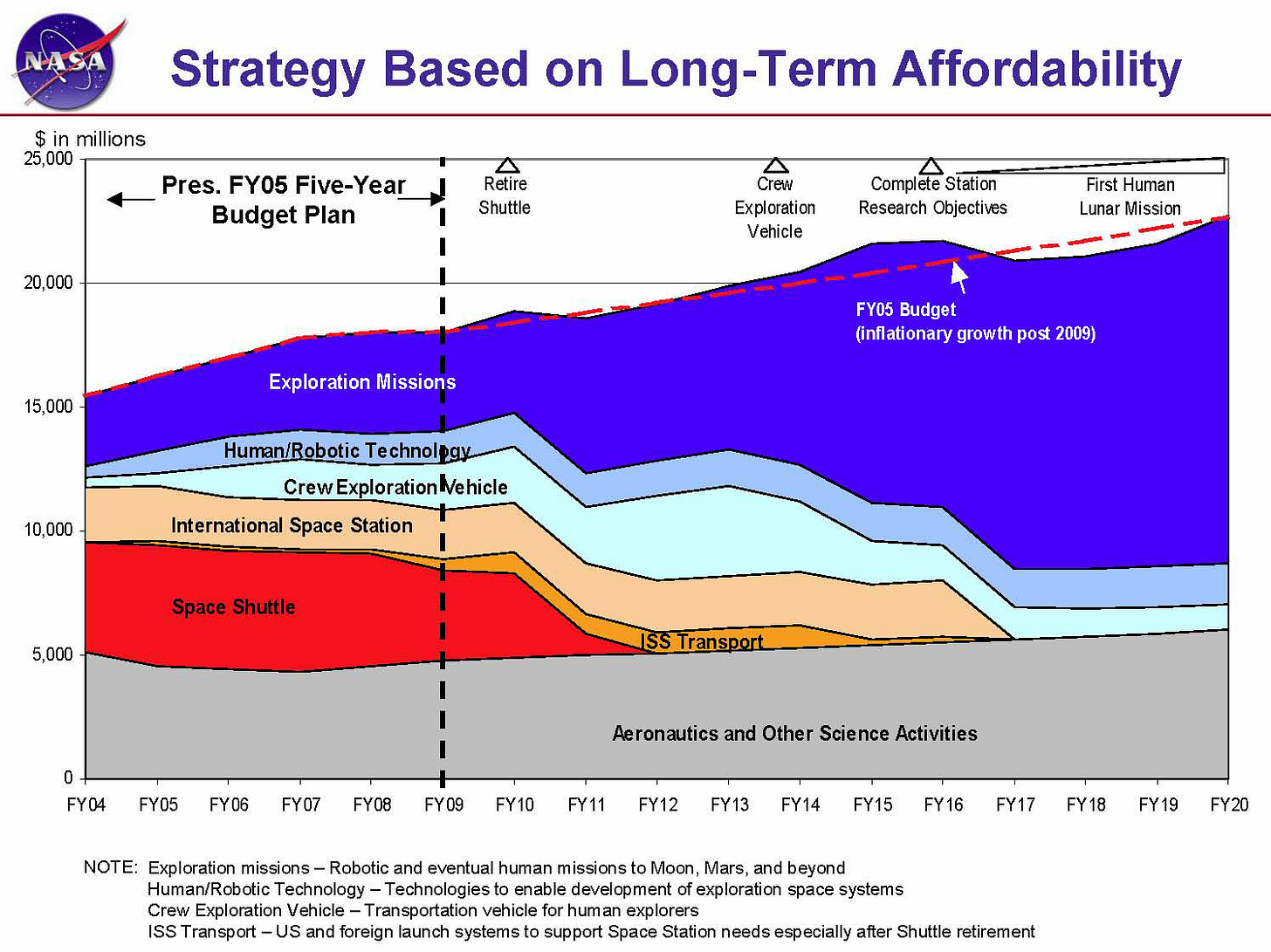

The so-called “gap” post-Shuttle was part of the Bush administration’s Project Constellation. In 2004, that administration foresaw a minimum four-year gap where NASA would rely on Russia for International Space Station crew rotations. But Bush planned to deorbit the ISS in 2015, so Constellation had no place for astronauts to go until a crewed lunar program was ready sometime circa 2020. Underfunding pushed back both timelines other than the station’s demise.

The Vision Sand Chart released by the Bush administration in 2004 showed a four-year gap after the end of Shuttle, and the end of the ISS circa 2015. Image source: NASA.

Obama’s Fiscal Year 2011 proposed NASA budget asked Congress for the money to save the ISS and fund NASA’s commercial crew program. Although commercial crew had been on the books since 2005, Bush never funded it. Obama asked for the funding, with a target date of 2015 for the first crewed flight.

In November 2013, NASA’s Office of the Inspector General (OIG) documented that Congress had underfunded the commercial crew program. The report concluded (page iv):

The Program received only 38 percent of its originally requested funding for FY’s 2011 through 2013, bringing the current aggregate budget shortfall to $1.1 billion when comparing funding requested to funding received. As a result, NASA has delayed the first crewed mission to the ISS from FY 2015 to at least FY 2017 … The combination of a future flat-funding profile and lower-than-expected levels of funding over the past 3 years may delay the first crewed launch beyond 2017 and closer to 2020, the current expected end of the operational life of the ISS.

Trump simply inherited the Obama program. And took credit for it.

The Obama administration issued its National Space Policy on June 28, 2010. Some Trump’s policies actually trace back to Obama.

For example, Trump tries to take credit for space nuclear power system development, but Obama’s policy had it in 2010 (pages 8-9).

Obama directed NASA to send crews beyond the moon to Mars (page 11). His administration did not, however, ignore the moon or cislunar space. They left lunar exploration to the private sector, through a program called NextSTEP — Next Space Technologies for Exploration Partnerships.

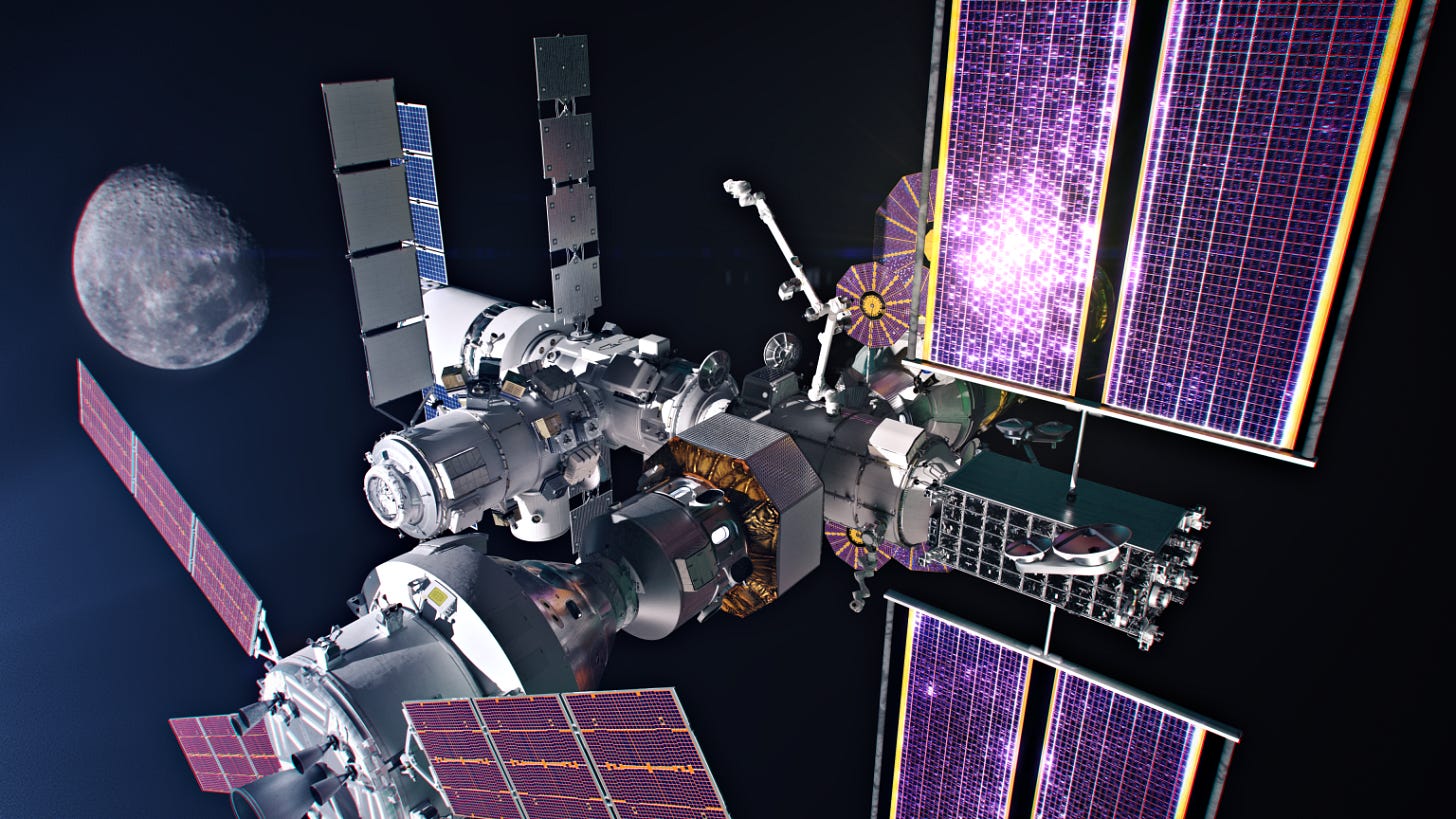

Obama’s administration proposed sending crews beyond the moon on an Asteroid Redirect Mission. Trump’s first administration pulled the plug, but some of the ARM technology made its way into NASA’s Gateway, the first cislunar space station.

Gateway, NASA’s planned cislunar space station, began under the Obama administration’s NextSTEP program. Image source: NASA.

Trump also pulled the plug on the crewed Mars program. His Space Policy Directive-1 modified Obama’s 2010 policy by redirecting NASA back to the moon “with commercial and international partners” as a step towards sending humans “to Mars and other destinations.” It deleted one paragraph from the 2010 document, which set 2025 as a date for crewed missions beyond the moon, including an asteroid, and for sending crew to Mars orbit by the 2030s. That paragraph was replaced by one that simply directed NASA to “lead the return of humans to the Moon” with no timeline to be met.

As for Project Artemis, it’s basically NextSTEP combined under one title with the Space Launch System and the Orion spacecraft. The name was announced by Trump’s administrator, former Oklahoma congressman Jim Bridenstine, on May 13, 2019.

Trump is taking credit for moon base plans that were already in the works long before his second term. This April 2020 NASA press release talks about plans for an “Artemis Base Camp” that were continued and refined during the Biden administration. Biden’s White House in November 2022 released its National Cislunar Science & Technology Strategy, which stated on page 2, “The Moon is a driver of scientific advances and potential economic growth.” Page 6 discusses a permanent human presence on the surface, in cooperation with US spacefaring partners, as well as economic growth in orbit and beyond.

The general public, unaware of this history, is being told by Isaacman that Trump conjured all this. Trump did not. This calls Isaacman’s credibility into question.

Show Me the Money

NASA’ proposed Fiscal Year 2027 budget should be released sometime in Spring 2026. That document will be Isaacman’s first opportunity to put on paper how he intends to accomplish all that he’s promised.

Trump’s Republican party controls both houses of Congress, but they went along with his plan to slash NASA’s budget by a fourth.

Senator Ted Cruz (R-TX) introduced legislation that restored some of the cuts, mostly to protect Project Artemis funding. That was included in Trump’s “One Big Beautiful Bill” that passed in July. The legislation requires NASA to use Space Launch System through at least Artemis V, a mission planned for circa 2030.

Pretty much everyone acknowledges that SLS is a boondoogle, but Congress hasn’t shown the courage to phase it out. SLS legacy contractors have very generous lobbyists on Capitol Hill, and perpetuate jobs across the nation.

Once SpaceX’s Starship and Blue Origin’s New Glenn are operational, hopefully some administration will show the courage to cancel SLS.

During his December 3 confirmation heading, Isaacman suggested that commercial options might be available after Artemis V — but that mission, of course, is long after the end of the second Trump term.

Isaacman, in my opinion, seems sincere. But I continue to worry that he’s a political neophyte who has no experience dealing with politicians that gladly torpedo reformist programs in order to protect obsolete jobs in their districts and states. That’s why commercial crew ran years behind schedule.

When the FY27 budget proposal is released, we’ll have a better idea how he intends to achieve the reforms he’s promised. The real test will come in the months thereafter, when the members of Congress largely ignore him and do what they feel like.

If Trump isn’t willing to back him, then nothing will change.

Thanks for this. It does not surprise.