Pluto is Not a Planet

Ninety-five years ago today, the Lowell Observatory announced they'd discovered the ninth planet. They were wrong.

The New York Times on March 14, 1930 reported the announcement a day earlier by the Lowell Observatory that it had found the ninth planet in our solar system.

Percival Lowell was a mathematician by education, and a businessman by profession. His knowledge of astronomy was largely self-taught.

In 1894, Lowell founded an observatory in Flagstaff, Arizona so he could study Mars. Lowell declared in 1907 his belief that intelligent life existed on Mars, and that he had photographs of canals “in the antarctic and south temperate zones.”

Lowell’s findings were instantly debunked by the Royal Observatory in Greenwich, London, England. The Chief Assistant Astronomer Royal told The New York Times that “we are inclined to believe that Mars is played out.” If there were once life on Mars, it died out millions of years ago.

In 1896, two years after opening the observatory, Lowell claimed he had observed spokes on Venus. The astronomical community rejected that finding too. A modern explanation is that Lowell saw shadows cast by the retina of his eye on his telescope’s pinhole.

Lowell passed away in 1916, but the Lowell Observatory remained. The staff continued Lowell’s pursuit of a “Planet X,” a hypothetical ninth planet beyond Neptune. Mathematical calculations showed perturbations in the orbits of Uranus and Neptune. Lowell and other astronomers concluded that another planet’s gravity might be responsible for altering their orbits.

The search for that hypothetical ninth planet led to the discovery of a celestial object by Clyde Tombaugh, a young astronomer who at age 23 arrived in Flagstaff. He was assigned the task of looking for Planet X, formally known as a “trans-Neptunian object.” Tombaugh used photographs taken over several nights of the same section of the sky to look for anything that moved. The math suggested the general size and location of where Planet X might be.

On February 18, 1930, Tombaugh found images he thought proved what they’d been looking for — a trans-Neptunian object moving in the night sky. This wasn’t a star. It had to be, they assumed, a planet.

A month later, on March 13, 1930, the Lowell Observatory staff announced to the world that they had discovered Planet X. They named it Pluto.

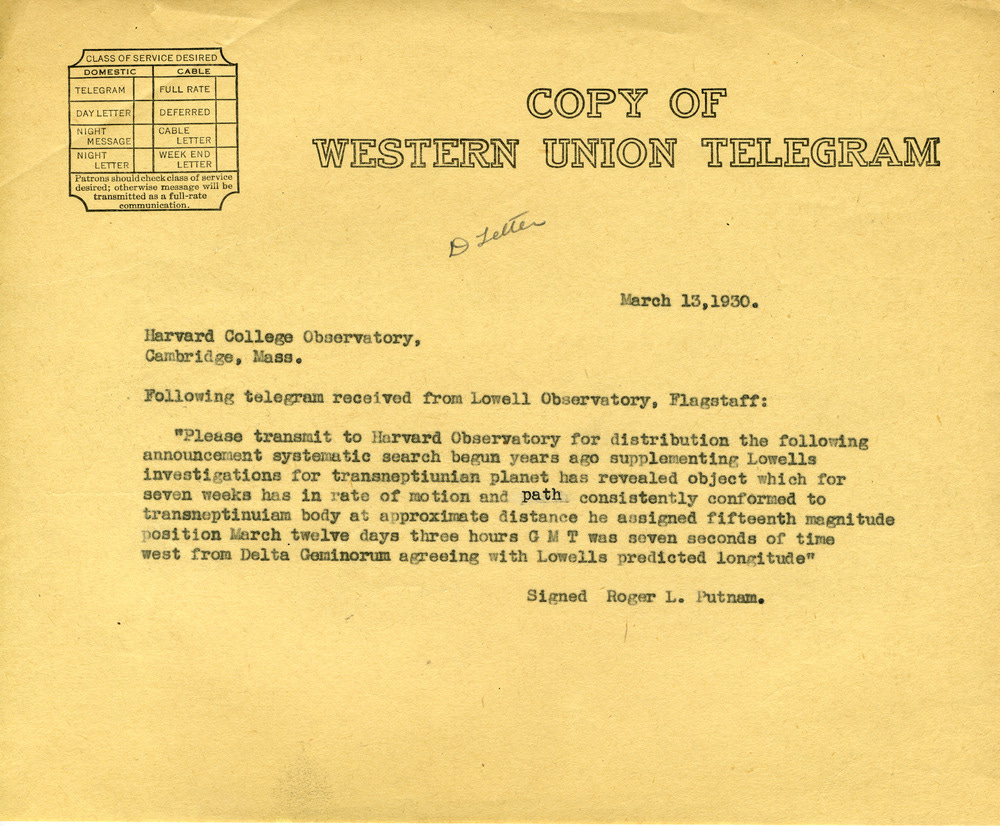

A March 13, 1930 telegram from Lowell Observatory trustee Roger Putnam to the Harvard Observatory reports finding a “transneptunian body” that agreed with Percival Lowell’s predictions. Image source: Lowell Observatory Library & Archives.

Other astronomers quickly questioned the conclusion that Pluto was a planet. The director of the Yale University Southern Astronomical Station told The New York Times that the object did indeed exist but, “… the object discovered is too small to create the disturbance that is taking place.” An astronomer at the Greenwich Observatory acknowledged it might be a planet but, “its orbit is quite unlike that of any major planet’s.” Its orbit was more like a comet or one of the hundreds of “minor planets” already known to orbit the sun. A South American Union astronomer told the Associated Press that the object was only one-thirtieth the size of Earth and forty times farther from the sun than Earth.

In retrospect, all these clues should have been enough to suggest that something else might be going on — but the technology didn’t exist to find out what that was.

By the end of the 20th Century, technology had caught up. As early as 1951, astronomer Gerard Kuiper at the University of Chicago suggested that an icy belt of “proto-planets” might exist beyond Neptune, where Pluto was. In 1978, astronomers discovered that Pluto has a satellite named Charon; the two were in orbit around one another. In the 1990s, a number of objects were found in the region, starting with Albion in 1992.

The region is now called the Kuiper Belt after Gerard Kuiper. More than 2,000 trans-Neptunian objects have been catalogued. Some, like Pluto, orbit around other objects. Some astronomers believe there may be hundreds of thousands of objects more than 100 kilometers wide in the Kuiper Belt.

The discovery of Eris in 2005, credited to data collected by CalTech astronomer Mike Brown, finally forced the issue. Eris is believed to be slightly larger than Pluto, but with less mass. If Pluto is a planet, should Eris be a planet? Is Pluto, or any other KBO, a “planet”? What is a “planet”?

The International Astronomical Union in 2006 decided to resolve the issue by creating a new category, called “dwarf planet.” The distinction is that large planets “clear their orbit” by colliding with orbital objects of similar size; moons orbit around the planet but cannot collide with the planet. A dwarf planet may share its orbit with other objects; it’s so small that collisions are rare.

The definition is imperfect. The IAU currently recognizes five dwarf planets — Pluto, Eris, Ceres, Makemake, and Haumea. It’s possible that more may be added by the IAU in the future.

The IAU is only an advisory body. It cannot force you to call Pluto a dwarf planet. You can call Pluto a planet if you want. You can call it Fred if you want.

If Clyde Tombaugh had the technology in 1930 to view the Kuiper Belt in its entirety, he would have seen thousands of icy balls. Pluto would not be unique except for its larger size relative to the other KBOs. But let’s put Pluto in context — it’s smaller than Earth’s moon, about two-thirds the moon’s diameter. Should our moon be a planet?

Good science is self-correcting. Percival Lowell was well-intentioned, but tended to see what he wanted to see. Science corrects itself through peer review. In the end, peer review proved that Lowell was wrong about life on Mars and spokes on Venus. His observatory was wrong about Pluto being Planet X. Science eventually corrected itself about the definition of a planet.

The search for Planet X continues. Mike Brown, whose work led to the discovery of Eris, believes that Planet X is out there. He calls it “Planet Nine.” Will he be remembered for finding this elusive planet? Or will he be the next Percival Lowell? Science will decide.

A 2024 presentation by astronomer Mike Brown to the Astronomical League of the Philippines discusses the possibility of a “Planet Nine.”

For extra reading, you may enjoy Mike Brown’s 2012 book, How I Killed Pluto and Why It Had It Coming. It’s for the lay person and lots of fun to read. You can buy it through the Palomar Observatory Gift and Book Store.