Losing NERVA

Project Apollo's road not taken might have used a nuclear engine to send astronauts to the moon. Six decades later, NASA still dreams of nuclear propulsion.

A 1970 NASA design concept for the NERVA nuclear rocket engine. Image source: NASA Glenn Research Center.

President John F. Kennedy, on May 25, 1961, proposed the United States send a man to the moon by the end of the decade and return him safely to the earth.

How to do it? That was a little vague.

The Democratic junior senator from the Commonwealth of Massachusetts had campaigned in the 1960 presidential election on the allegation that the Republican Eisenhower-Nixon administration had allowed a “missile gap” with the Soviets ahead of the US. This wasn’t true but, after he took office on January 20, 1961, Kennedy inherited the so-called “gap.”

Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarian launched from Baikonur on April 12, 1961, becoming the first human to orbit Earth. Less than a week later, the US-backed invasion of Cuba at the Bay of Pigs failed.

Kennedy felt he needed to prove he was doing something about supposed US inferiority in space. On April 20, Kennedy sent a memo to Vice President Lyndon Johnson, who chaired the National Space Council. Kennedy tasked Johnson “to be in charge of making an overall survey of where we stand in space.”

As president, Kennedy would have been briefed about government research and development of various rocket propulsion technologies. At the time, rockets and missiles typically were propelled by chemical reactions, such as liquid oxygen mixing with RP-1 kerosene, or solid fuel mixtures used in certain ballistic missiles.

But other options were possible. Ever since the Atomic Age began in 1945 with the Manhattan Project at Los Alamos, theoretical physicists had dreamed of using nuclear energy for rocket propulsion. By 1955, the Los Alamos Scientific Laboratory was working under contract with US Air Force and the Atomic Energy Commission (AEC) on a nuclear thermal propulsion (NTP) program called Project Rover.

The Rover contract was transferred from the USAF to NASA when the new agency began on October 1, 1958. NASA had evolved out of its predecessor, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics, which was a think tank for the US aviation industry. NASA was to be the same for aerospace. The NACA was already looking at aircraft nuclear propulsion when it was absorbed by NASA.

An undated 1960s Los Alamos lab film about Project Rover. Video source: Los Alamos National Lab YouTube channel.

By the time Kennedy took office on January 20, 1961, Los Alamos already was conducting ground tests of a NTP prototype called KIWI. NASA and the AEC awarded contracts to Los Alamos for successor programs, such as the Nuclear Engine for Rocket Vehicle Application (NERVA), and the Reactor in Flight Test (RIFT) to place NERVA in space.

When Kennedy sent his April 20 memo to Johnson, one of the questions he asked was:

In building large boosters should we put our emphasis on nuclear, chemical or liquid fuel, or a combination of these three?

Johnson’s written reply came eight days later, on April 28. In response to Kennedy’s propellant question, he wrote:

It was the consensus that liquid, solid and nuclear boosters should all be accelerated. This conclusion is based not only upon the necessity for back-up methods, but also because of the advantages of the different types of boosters for different missions. A program of such emphasis would meet both so-called civilian needs and defense requirements.

When Kennedy addressed Congress on May 25 to propose his crewed lunar program, he listed four “national goals.” The first was:

I believe that this nation should commit itself to achieving the goal, before this decade is out, of landing a man on the moon and returning him safely to the earth.

This goal eventually adopted the name of an already existing NASA crewed lunar spacecraft program called Project Apollo.

All but forgotten was the second:

Secondly, an additional 23 million dollars, together with 7 million dollars already available, will accelerate development of the Rover nuclear rocket. This gives promise of some day providing a means for even more exciting and ambitious exploration of space, perhaps beyond the moon, perhaps to the very end of the solar system itself.

It was around this time that NASA was finalizing a contract with Aerojet General and Westinghouse to manage NERVA. The program was to build on KIWI with the objective of launching a functioning NTP engine into space.

In those early days, the launch vehicle for Apollo was anything but clear. Wernher von Braun and others had been working on a series of next-generation booster ideas named Saturn. A group called the Silverstein Committee (after NASA executive Abe Silverstein) had looked at various options for combining a powerful new Saturn first stage booster with various upper stages to create a super-heavy lift vehicle. It was possible that one or more of those upper stages might have a NTP engine.

Von Braun had expressed public and private support for NTP technology, but Kennedy had set the end-of-decade deadline. In an April 29 memo to Johnson, von Braun wrote, “… there can be little doubt that the basic technology of nuclear rockets is still in its early infancy … It should not be a serious contender in the big booster problem of 1961.”

Von Braun suggested that a nuclear rocket might be more appropriate as a Saturn successor “… in the years beyond 1967 or 1968.” Another super-heavy booster program running in parallel to Saturn was called Project Nova. A January 1959 NASA report for President Eisenhower foresaw Nova as “competitive” to the Juno V, an earlier name for Saturn. The report described Nova as “the first vehicle of the series that could attempt the mission of transporting a man to the surface of the moon and returning him safely to the earth.” In December 1960, while Eisenhower was still president, an ad hoc panel produced a report suggesting that Nova might have “a suitable nuclear upper stage.”

If the nuclear development should be as successful as its proponents hope, it might open the way for future developments beyond the possibilities envisioned for chemical rockets. However, a sound decision on the promise of nuclear rockets cannot be made until about 1963.

The August 25, 1961 front page of the Orlando Sentinel reported that north Merritt Island had been chosen for “Project Nova.” Image source: Newspapers.com.

Various Florida newspapers reported on Project Nova. A July 12, 1961 Associated Press article published by the Miami Herald reported a plumbers strike at the AEC’s south Nevada test site was delaying Project Rover, “part of the 90 million dollar project Nova to put a man on the moon via a nuclear rocket.” A July 18, 1961 Miami Herald article reported that the Saturn at Cape Canaveral would be used to orbit three men around Earth and then the Moon, but Nova “would be used to land three men on the moon and return them to earth.”

The August 25, 1961 Orlando Sentinel front page trumpted the selection of Merritt Island for Project Nova. The Sentinel published several articles that day about Nova and its impact on the local economy, but none of them mentioned nuclear propulsion. One article did distinguish between Saturn and Nova class boosters.

Nova was still a viable project two years later. NASA called a “program plans conference” with its industrial contractors for Washington, DC on February 11-12, 1963. The conference produced a report of the various presentations.

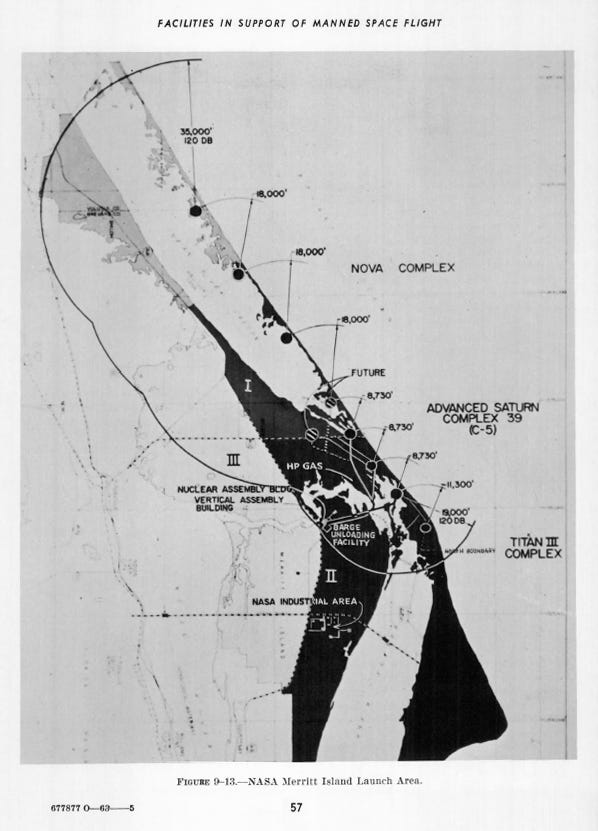

The February 1963 Program Plans Conference book had a map showing plans for a Project Nova complex northwest of the Saturn pads, as well as a Nuclear Assembly Building near what was then called the Vertical Assembly Building. Image source: NASA-Industry Conference Program Plans.

The report described Nova as “either a liquid or solid rocket or perhaps Saturn V plus a nuclear stage.” It noted that no funding had been requested for building Nova hardware. The report forecasted, “In the last half of the decade, we expect to flight-test … the nuclear thermal engine Nerva in the Rift spacecraft stage, and prior to 1970 we expect to accomplish the Apollo mission for landing man on the moon and returning him safely to earth.” There were discussions about using Nova for next-generation missions to the planets, but not for the crewed lunar program.

NASA’s NTP project became a victim of its time. Although NASA had dreams of sending humans beyond the moon, the presidents of the 1960s and Congress did not. Budget reductions began during the Johnson administration in 1967, with Congress inclined to cancel NERVA entirely.

By the early 1970s, the Nixon administration had suspended development of the NERVA engine. In a January 24, 1972 letter to the chair of the House Committee on Science and Astronautics, NASA administrator James Fletcher wrote that NERVA was being terminated in favor of a much smaller nuclear engine. The need for NERVA was not foreseen until at least the 1980s. The smaller engine might one day compete with traditional chemical or solar propulsion systems for payloads to the distant planets in the solar system.

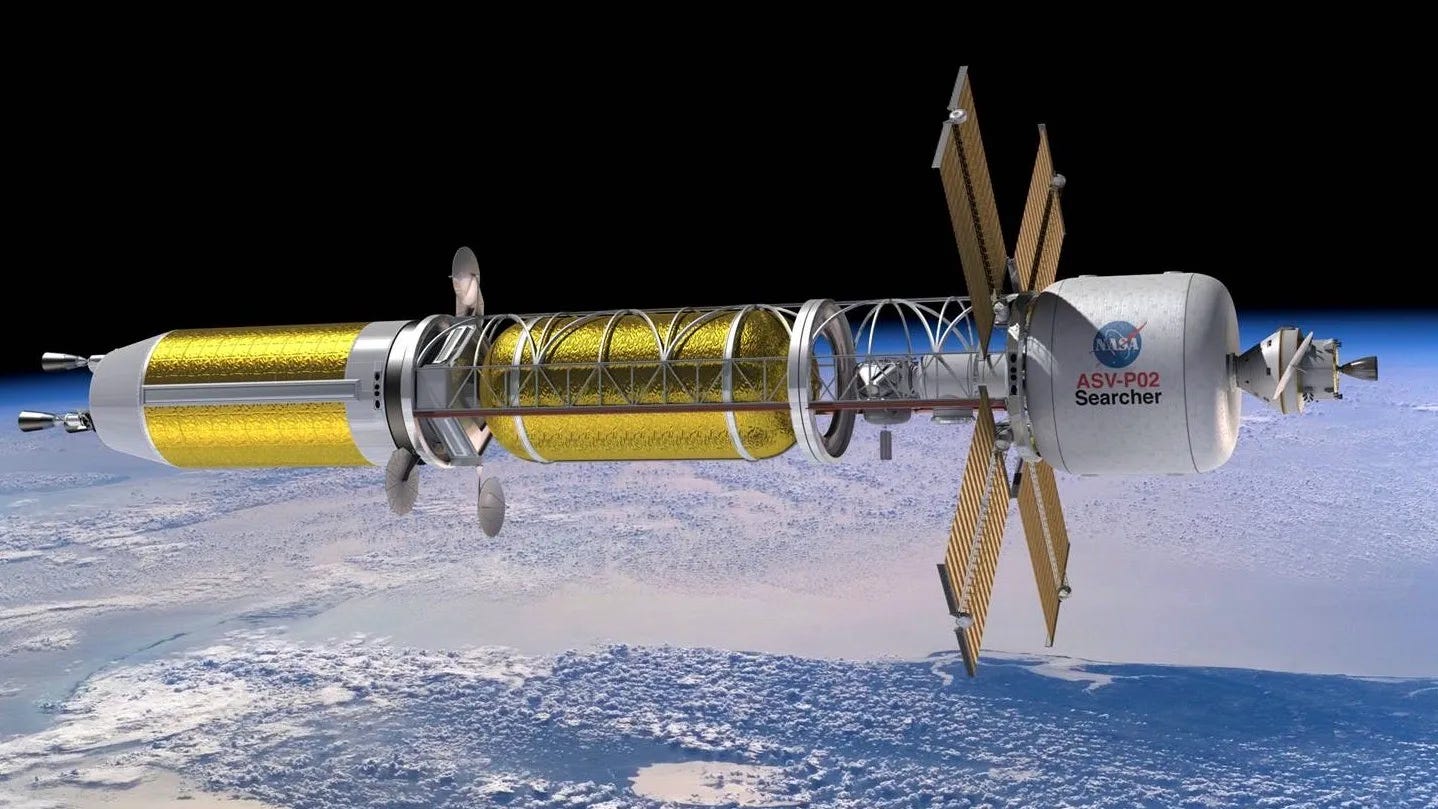

An artist’s concept of a spacecraft powered by nuclear thermal propulsion. Image source: NASA.

In the 21st Century, NASA still dreams of developing a nuclear propulsion engine. The Space Nuclear Propulsion (SNP) office researches both nuclear thermal and nuclear electric propulsion. In 2021, NASA awarded three reactor design concept contracts at $5 million each to three companies. The Langley Research Center in Virginia is working on a nuclear engine radiator called MARVL as part of a vision for sending humans to Mars one day.

In his April 9, 2025 opening statement during his confirmation hearing, NASA administrator nominee Jared Isaacman said:

We will focus our technology development efforts on the world’s greatest engineering challenges, such as the practical application of nuclear propulsion, so that we can truly unlock humankind’s ability to explore among the stars.

Talk is cheap. Space is not. Isaacman was most likely sincere, but he has to navigate political limpet mines, starting with the White House Office of Management and Budget. The initial Fiscal Year 2026 NASA budget proposal would cut $531 million from the Space Technology budget, “including eliminating failing space propulsion projects.” But the proposal would introduce “$1 billion in new investments for Mars-focused programs.” The budget proposal, apparently developed without Isaacman’s participation, will then have to go through the congressional sausage grinder.

Perhaps the only way to assure NASA gets to build a nuclear engine is for China to demonstrate one. The fear of the Soviets beating the US to the moon prompted Kennedy and Congress to spend billions on Apollo. Maybe China demonstrating a nuclear engine might do the same trick. The South China Morning Post claimed on March 19, 2024 that a research team’s “prototype lithium-cooled nuclear reactor system has passed some initial ground tests.” The article said that “China has made significant strides towards interplanetary travel with the development of a nuclear fission technology that could power large-scale exploration of Mars.” The claims have not been independently verified.

2025 is not 1961. Some politicians have claimed the US is in a new “space race” with China, but few people seem to care. Even if China were to develop a nuclear engine, for what missions would it be used? That was the same question that doomed NERVA — no mission for its use was on the horizon.

Protestors attempt to breach the Cape Canaveral Air Station security fence on January 18, 1987. Image source: Florida Memory.

Nuclear powered missions tend to attract political protestors. One example was a mass demonstration outside Cape Canaveral Air Station on January 18,1987, protesting an upcoming test of a Trident II missile designed to deliver a nuclear weapon to an enemy target. According to the Florida Today report the next day, the rally attracted 4,000 protestors. 138 protestors were arrested, some of whom tried to scale the station’s security fence.

Demonstrators showed up to protest the launch of the NASA Cassini-Huygens mission from Cape Canaveral on October 14, 1997. Protestors objected to any use of nuclear power, by NASA or the military. Some believed that the launch would somehow fail and poison the area with plutonium. A much smaller group of about 30 showed up in January 2006 to protest the New Horizons probe to Pluto, also fearing the use of plutonium fuel.

Authoritarian regimes don’t have these problems. If those in charge decide to proceed with the project, it moves forward regardless of public objections or the lack of political support.

If those in the new administration wishes to prime the pump for a new nuclear engine project, they will have to find a way to convince Congress to fund it beyond the next election cycle. The supporters of NERVA and nuclear thermal propulsion never found the answer. Foresight is a rare commodity in politics.